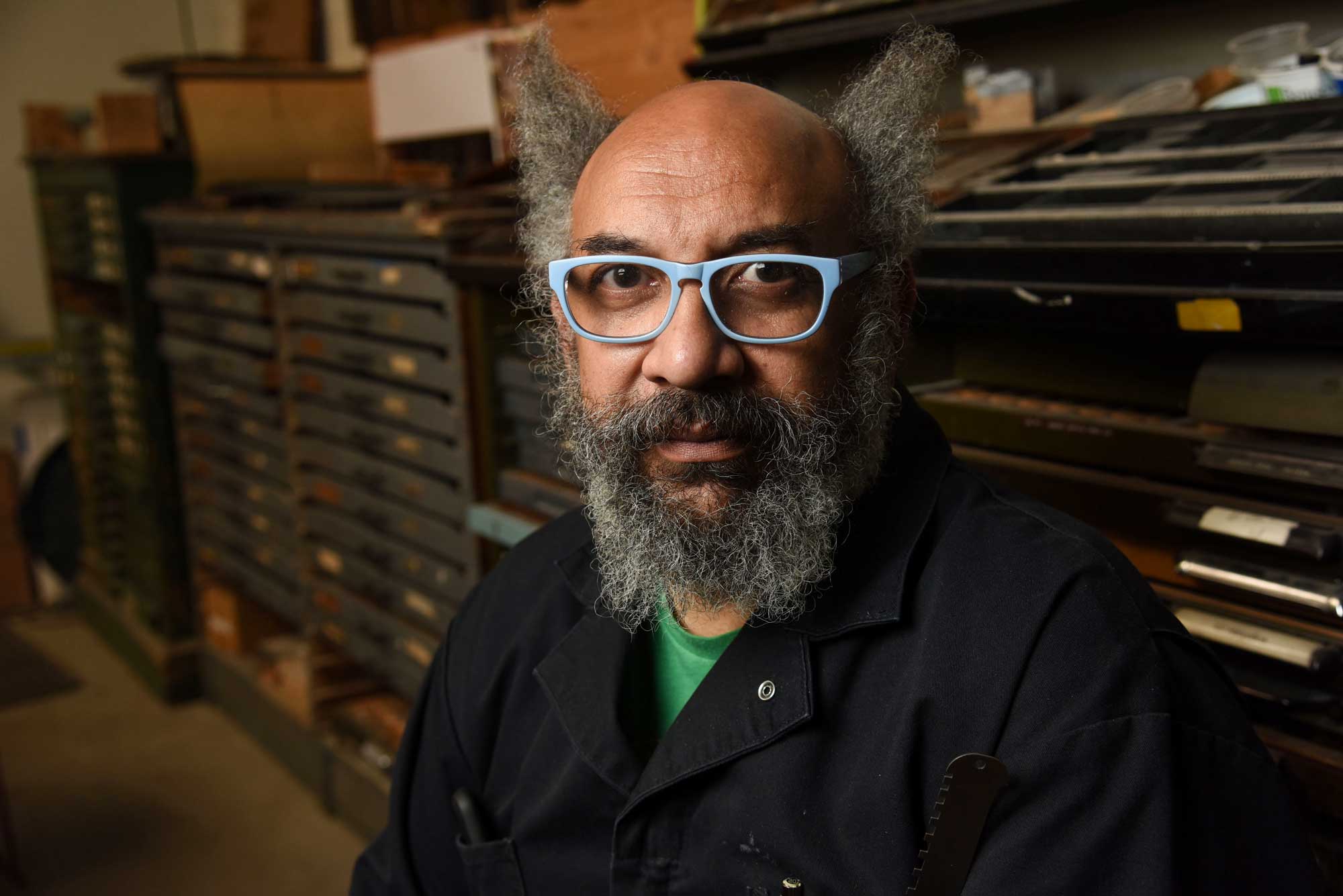

The following conversation took place in Denver, Colorado shortly before Hugh Weber’s untimely passing. In honor of his final interview, we’re publishing much of this conversation with Rick Griffith digitally, with an extended iteration coming out in our print issue, later this year.

I wouldn’t ask this question of most people on the front end, but have you ever read Martin Buber? He was an Austrian philosopher and Jewish mythicist, and he wrote a book called I and Thou. He conceptualized that most of the world is constructed of I-It, which is to say person and subject, this distance and disconnect. And that in the I-Thou construct, there’s a mutuality where the actual relationship is the thing. Neither exists without the other. It’s a headspace that I’ve tried to be in during these TGD conversations.

What’s most important is that we consent to a relationship. Like you said, you’re prepared to be overwhelmed. That’s fantastic. Because we have a lot of shit going on here, and some of the things I think of are sometimes overwhelming, and that’s my way of humbling myself and sometimes inviting people to share that, it can humble them too.

Touching on an idea that I discovered in a book that’s super helpful for my nature, is thinking about something that’s relatively unrelated, and transposing one kind of wisdom or one kind of idea into another space and really learning from it. It can be super humbling. Because you have to make room to be wrong.

That level of awareness requires continued commitment to acts of courage, whether it’s with a big capital C, underlying courage, or just mundane.

Regular courage is fine. Regular courage makes me weak on the regular. I’m like, God, did you see that courageous act? That is too much for me. One human being just did that, [I’m] fucking floored. And it starts with the courage of the people who survived, who are surviving, the attempted genocide on the First Nations of this country, of this continent. It starts with people who are willing to speak truth to power. It starts with people who are incarcerated and ultimately trying to fight a system that has been unjust. Courage is crazy abundant.

This week, what are things that you’ve seen or moments that you’ve had of that?

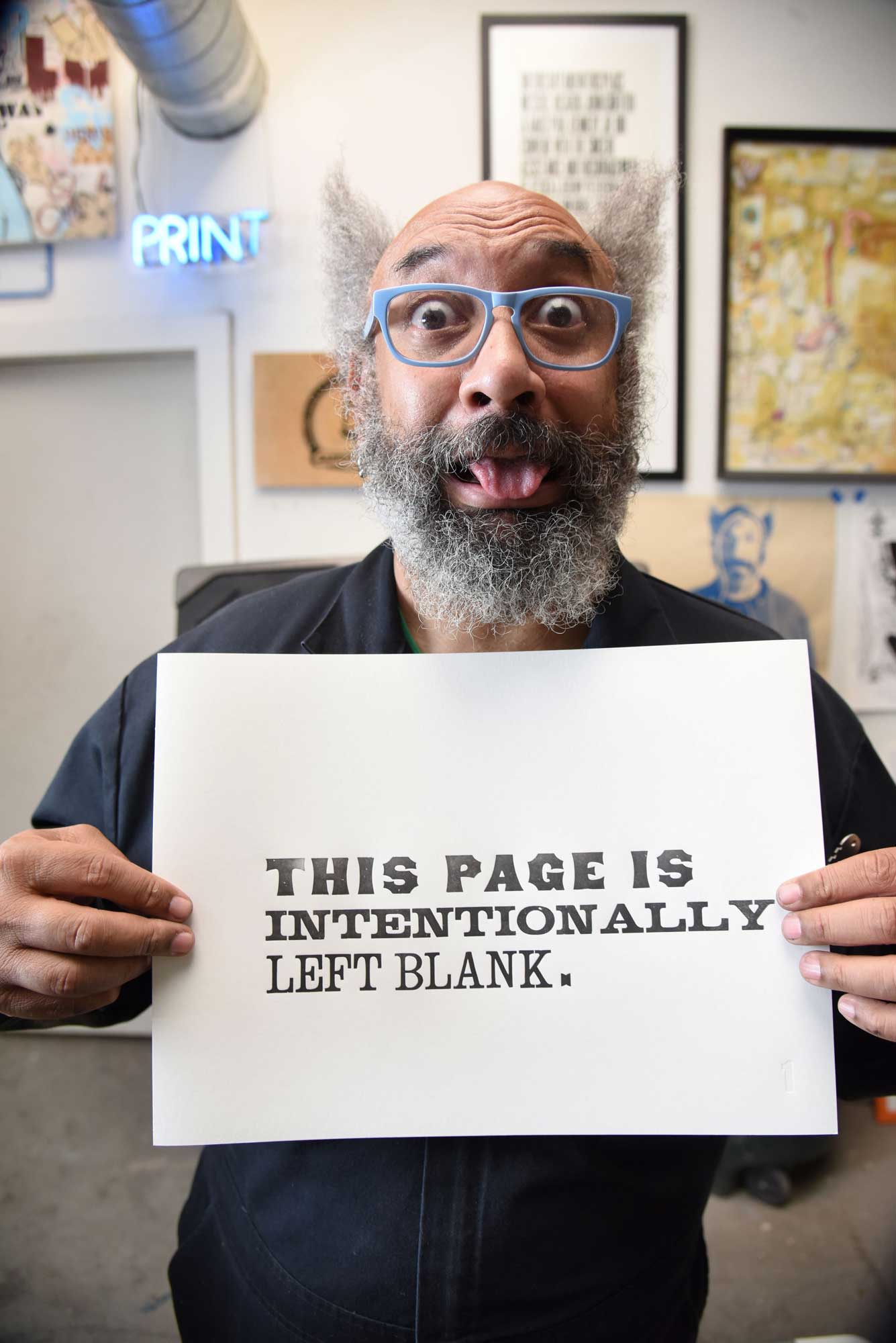

Like a broken faucet, there’s a constant drip of experiencing other people when you own a store. The store is a project, it’s a design project, and as designers, it teaches us how fast something can change or how slow it has to be to change while it’s in the public right of way. It teaches us how people behave when they are seen and acknowledged and they come from historically marginalized groups of people.

The regular drip of courage that shows up in my life is because most people who walk into this store have an awareness of where they are, and they come in and they breathe in the space. Everyone who works here knows we’re not in the book-selling business. We’re in the acknowledgment business. Because every single human being that walks in here is ready to get their learn on and we’re all about it. That level of encouragement is so critically important for people. And, it’s modeled after the kind of bookstores that I grew up learning design from in New York.

I was getting my learn on, I was starting to acquire a certain track of knowledge. And my big skill, I don’t think it’s design—although it’s becoming design. My biggest skill is the interrogation. I know how to ask questions, and that’s why I’m a self-taught person. That’s my fortunate life, people have helped me be in the right place and I’ve known how to ask the right questions, and it’s turned into a career of listening and being guided by particular people and understanding. Like, right now I believe I’m getting a grip on understanding the role of form making and art in design, understanding the need for abstraction, for modeling, understanding the need for bringing people to bigger ideas that are participatory and saying, “How do you want to play?” Taking the idea of competition and inverting that to mean much more collaboration.

I’m curious what it looks like when someone walks into the store and doesn’t know where they are.

People are like, “Hey, do you have any Agatha Christie? My mom really needs a good murder mystery.” I’m like, “God, we don’t do that.” I used to say funny things like, “We don’t have a historical fiction section, because historical fiction is the enemy of reality and truth.” But I’ve shaken loose quite a bit of sarcasm and cynicism, and I come to the world quite honestly if I can. And earnestly. I don’t want to fuck this up. I want to portray an awesome person who’s working hard. I want to be worthy of other people. But also, if that’s all I cared about, I’d be fucking nowhere right now.

So, I do feel like being worthy of my own best judgment is good enough, and that’s what I got to lean into. My partner says that I’m neurodivergent, and I go, “Would you like me to be medicated? Is that helpful to you?” And she said, “No. You’re beautiful the way you are. It takes energy and work to be with you.” And I go, “Okay, cool.” And I always silently say to myself, if someone’s spending that energy and work to be with me, that’s an act of love. I find that to be fantastic. And so, I also think of how I embrace other people—what that agape looks like for me. Being really well-loved is pretty much instructive. If you understand the various ways that love is transmitted to you, you’re capable of transmitting that back out in the world.

Where did that awareness come from? What did that journey look like?

I grew up in Southeast London, and immigrated to the United States with my family. I left home relatively young. I dropped out of high school. I just sort of stopped showing up. There were other more important things to do. And then I lived in DC. The DC punk scene in the ’80s took me in, which was really one of my most favorite experiences in my whole life—having access to divergent thinkers. In the early ’90s, I left punk DC for punk, queer New York and the East Village. I met my girlfriend who would become my wife and then she found Boulder, Colorado, and was like, “I want to live in this place.” I said, “Okay, give me a year. I’ll figure it out.” So somewhere in the mid-’90s I showed up here and traveled between New York and here ever since.

When you came this way, were you already designing?

Well, I like to think of my time working in the Kinko’s, coffee shops, and shit like that, as doing that work. I worked at the Kinko’s at Columbia University during the period of the Black Rock Coalition with Living Color, and the Bad Brains were making Black punk rock. So, I was doing some punk flyer support for bands at that time, and it was just a great experience.

You said you feel like you’re just figuring out design. What have you learned recently that feels like a tipping point?

All sorts of stuff emotionally, for sure. Being so in love with what I’ve learned from Terry Irwin and her husband, Gideon [Kossoff], and their entire early cohort of thinkers in that space. Your life can change in the middle of your career, and I think that what Terry has made a priority has basically helped change my sense of priority in this life. I have two things going for me in that regard. I’m Black. One of the great things about being Black is I have this Black experience. I can look at something like Transition Design and I can say, “Oh yeah, baby, all day.” And if you try and do design to me, I’m going to fucking resist. I’m going to resist you doing design to other people. Now I’ve got the language to figure out how to stop you from using design as a weapon or an instrument of bad action. Because there is a mechanism here that shows us how to be inclusive, how to get the knowledge from the people who are closest to the circumstance that you are trying to resolve instead of fucking around. That’s why I say that our bookstore’s a design project. Because if the wicked problem is how to transition into more socially equitable experiences based on your geography and the people who are present in it, one of the things you do is you make community for them. You make spaces for them to convene. And when I say “them,” I mean the people who also want a more equitable and open, socially conscious community. Because all we’ve got to do is step out of our own bullshit for five fucking minutes and you get it.

You’re like, “Oh, I get how my action fucks up your shit, and I get how it doesn’t have to, and I get how my support is so important to you getting your shit done.” Like, you could no longer do the wrong thing because you have an awareness of the right thing. My mom would be like, “You know better.” Now I know what “You know better,” means, and it doesn’t come from this kind of soft altruism that lots of designers had been doing before. I heard about Terry’s own personal transformation and movement towards this work, but it’s not about working for non-profit organizations. It’s about making your assessment of the problem something that has action built into it, that has equanimity built into it, that has a participation of people closest to the circumstances that you’re trying to change in it.

Would you say your community exists beyond Denver?

When I was isolated here in Colorado, as soon as I could afford to, I invested in other communities—communities of people interested in type and design and going to type and design conferences. Going to learn, going as a student, has been what I’ve been doing for 30 years. I actively remember going to an exhibition in New York on the posters of Ivan Chermayeff. There were all these really witty, well-done posters for Mobil and all these oil producers—big giants of industry. I remember looking at that and being like, “Okay, that’s graphic design, got it.” I remember looking at Woody Pirtle’s “Hot Seat” poster and being like, “Yeah, that’s graphic design. Got it.” Then I ended up getting turned on to Abbott Miller and Ellen Lupton. The first time I saw them in person, 25 years ago, they released a book called The ABCs of Bauhaus. And I went to the symposium at Cooper Union, downtown. I remember listening to people there talk about design in ways that were super instructive for me. I remember Barry Deck being there. He had designed Template Gothic. That font had come out of studying with Ed Fella, at CalArts. It was one of the early Emigre fonts and Emigre was instructive. I have a very close to full set of Emigres over there in the library. All the things that participated in teaching me design are either products that I bought or things that I went to and experienced live in person that introduced me to other names of other people I could study and learn from. That’s why New York was such a crucial place and continues to be very important in my life.

I have a love affair with New York because Brooklyn is run by Black people. If you want shit done in Brooklyn, you’ve got to trust and care about the condition and the experiences of Black people. So, it’s exciting just to be in a place like that, where being Black is valuable. Because you speak that language of respect. Instant, absolute agape love for each other. You’re not stepping into a circumstance where you could be talking to someone who is actively working against you in their life.

I’ve had the privilege of spending some time in Detroit. It is such a foundationally different experience from everything that I’ve known. It’s beautiful. I love, selfishly, that feeling of walking through a space that’s not been made in the same way for me that a lot of spaces have been made for people that look like me. But also, to see how supportive it is to the creatives there. It is a remarkable thing. The city actually has a chief storyteller, his name is Eric Thomas. Amazing young guy. One of the first times I visited, he asked to meet. He walked in and he goes, “I just need to be upfront. I don’t fuck with white people.” I was like, great. That’s a good place for us to start.

I love that.

I did too. There’s such an honesty and a truth to it. And it allowed us to have a real conversation.

I absolutely fucks with white people. Because somewhere in my heart I sense that the liberation of the future generations of my people is linked to the psychic health of all people, including white people. Because if white people are psychically unfit, that’s a whole lot of white fuckery going on. So, I respect people who say that, because that clarity, that is a life with purpose. The challenge for me that is more true, is that I’m here to show, model, be in the river of this conversation about Black excellence and Black love, Black intellectuals and the need to not fear each other. So, cooperation and collaboration is really the answer and love is the answer.

It shifted quite a bit when Debra came along. Debra and I have had a lot in common for a really long time, but the big thing that we didn’t have in common for most of that time was that I was okay with being sarcastic. I was really good with leveraging wit in that way that is not super productive. It’s a hard reputation to shake. On a couple of occasions, I’ve had people be like, “That dude’s a full-blown prick.”

About you?

Oh yeah, for sure. Whether it came from being critically afraid of what I would do to the profession if I got my hands on it, or whether it’s because I was being a prick. That’s the stuff that changed. Debra shows up in my life and the lessons that I learned from her, and from the death of my wife, and from our experiences together are just shame and cynicism and sarcasm are bad. It’s kind of hard to get away from, but my lessons have been a continued expression of the idea that shame isn’t useful and cynicism isn’t useful and what do we do instead? How do we carve a path that’s different? So that’s what we do together now.

When I was prepping [to chat with you], I wrote down “acts of courage, acts of community, and acts of criticism.” It feels like the moment to ask about the third. Despite that absent cynicism, there’s still a place, especially in design, for considered criticism. I wonder what role you feel that plays in some of the work you’re doing currently and potentially as you become an elder in this profession.

I’m fine being patient and if people want to think this thing about me from the past, that’s fine—me being an asshole or a prick or whatever. But in the present tense, I’m more concerned with being in the community in a more productive way and how you deploy criticism is part of that. My historical thing about criticism is that it’s a gift and if people don’t want it, they can reject it. But the louder you reject criticism, the more it says about you.

When people criticize me, I internalize a lot of it. Sometimes it hurts because it is true; sometimes it hurts because it’s not true. My own method for being a critic of something has changed over the years. I try to be really generous intellectually, which means I spend a lot of words and time on each piece, talking about it. As a teacher, I might spend a lot of time trying to think about how to affect what prioritization people put on their thinking. So not just that they have a thought, but is that thought the first thing to think about when you’re solving this problem?

Once you get a reputation for living your life loudly and without some sort of sheath or cover, people will criticize you any way they see fit and they’ll also try and find faults in your logic and reasoning. All of those things I think are fair just because I understand how human beings like that sort of blood sport, but I don’t think of them as completely necessary. There are designers that do it for me and there are designers that don’t. There are people whose work I think is critically important and there’s stuff that I’m like, yeah, it’s okay.

“As a teacher, I might spend a lot of time trying to think about how to affect what prioritization people put on their thinking. So not just that they have a thought, but is that thought the first thing to think about when you’re solving this problem?”

Do you think about your place in that? Do you think of legacy in terms of 50 years from now or even 15 years from now?

Not a lot, but I hate to be misunderstood, that’s kind of my Kryptonite. Because there are layers to the way I think about stuff. There’s stuff that’s wildly imaginative that is mapped on stuff that is based on science, right? I’m just trying to borrow the frame from science and then hang some wildly imaginative ideas on the frame. I’d like people to know that I think that, that’s not just possible, but that that’s an obligation of creative people—to look at intersectionality and hang wildly creative ideas on frames that are respectable and grounded and just see what happens.

To the question of connection, when you think about the way your work is influenced and—I talk about them as ROIs, relationships of influence, these people that we go to in hard times, in celebratory times, we go to them with really complex problems, for honest feedback—do you have a cohort of designers or printmakers that you see as that cloud of wisdom around you?

I’m really attracted to a bunch of people and what makes them attractive to me is that they’re teaching intellectual generosity. So, when I meet people who have found inventive ways to share that seem like they’ve got some moxie, that’s exciting for me because I want to participate in it, but I also want to learn something from it. So, there are all kinds of positive influences out there. The most obvious to me is my family. They’re constantly changing, which keeps me so alive with the awareness of what they’re doing. It’s not always a positive thing, but sometimes it can make a positive idea alive in me, make it fresh in my head again, that we’re all changing, that we’re all shifting and moving through stuff.

In the world of other designers, I’ve become close friends with Debbie Millman. I feel heard by her and moved by what she’s up to. Louise Sandhaus is very, very special to me, her generosity for decades has been really, really supportive. David Reinfurt, it’s too creepy to say “hero” because he’s alive, he’s a human being, he’s a regular person, but there are things that David has done over the years that have made, and continue to make, so many other things possible for me. Muriel Cooper, the woman who was in charge of the Visible Language Workshop at MIT, has played a long, great role in my life so far. They have said, if you want people to understand the nature of visible language, you need to bring them close to the means of production and at that time, it was the printing press. I could think of no other reason to bring the printing press closer to me than the idea that I wanted to learn how it worked and how it behaved in the world of visual communications and as I was teaching myself how to be a designer, this became a critical aspect of it.

Teaching human beings, it’s a very, very generous and important act. To that end, there’s Brian Allen, this guy who taught me how to print, and Tom Parson. I was the youngest kid in the letterpress meetups, because they put me there—I was the 25-year-old kid that was learning to print.

My ambition as a designer started out like, I’m going to be the best graphic designer of all time. Then it changed from wanting to be the best graphic designer of all time to realizing that I wouldn’t be. So I put away the best possible graphic designer of all time and I said, “I want to be the person that loves graphic design the most.” And that’s where I’ve landed with whatever’s left of my competitive attitude about design. I want to be the person that loves it the most. So yeah, I’m actively looking for inspiration all the time—people to inspire me with their own acts of courage and to make me weep because it’s beautiful.

Feels like a final word.

It’s consistent for me, the courage to exist—it’s huge. People are dying by suicide all the time, dying from mental illness, dying from feeling like they have no place to be in community with people. So, courage to exist and to contribute and participate, it’s heavy shit and again, it would go a long way toward us not fearing each other or competing with each other if we spent more time validating each other and acknowledging each other and holding space for each other’s existence. Making us feel comfortable in that. Graphic design, it’s one of the ways that we solve that problem.