The Hausaland region of northern Nigeria was home to one of the largest textile industries in pre-colonial Africa, whose scale and scope were unparalleled throughout most of the continent.

As one German explorer who visited the region in 1854 noted, there was ‘something grand’ about this textile industry whose signature robes could be found as far as Tripoli, Alexandria, Mauritania, and the Atlantic coast. Centers of textile production like Kano were home to thousands of tailors and dyers producing an estimated 100,000 dyed-robes a year in 1854, and more than two million rolls of cloth per year by 1911.

Much of the industry’s growth was associated with the establishment of the empire of Sokoto in the 19th century, which created West Africa’s largest state after the fall of Songhai, and expanded pre-existing patterns of trade and production that facilitated the emergence of one of the few examples of proto-industrialization on the continent.

This article explores the textile industry of the Sokoto empire during the 19th century, focusing on the production and trade of cotton textiles across the Hauslands and beyond.

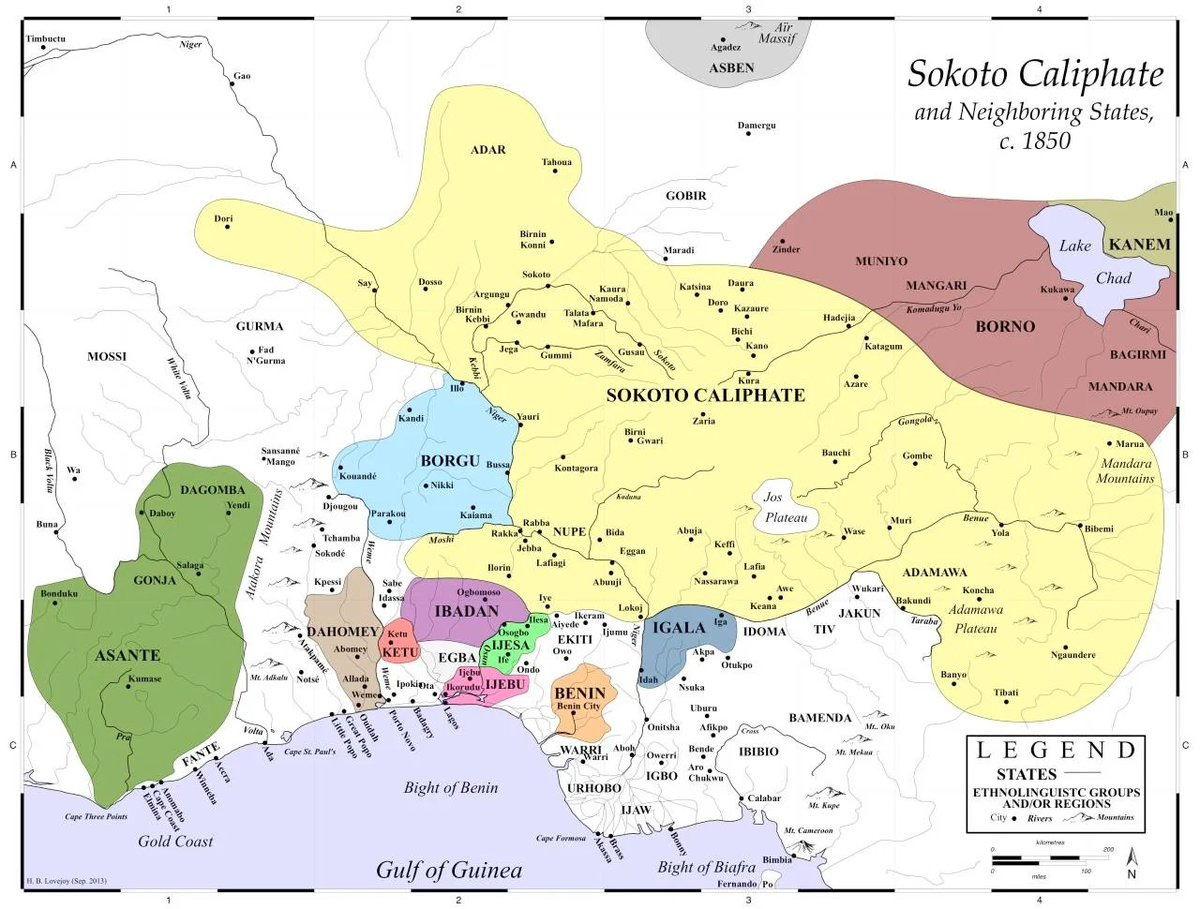

Map of the Sokoto Caliphate and neighboring states. ca. 1850, by P. Lovejoy.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

A brief background on the history and political economy of the empire of Sokoto.

In the early decades of the 19th century, a political-religious movement led by Sheikh Usman dan Fodio across the Hausaland region subsumed many of the old Hausa states into the Sokoto Caliphate, creating west Africa’s largest empire after the fall of Songhay. Headed by a ‘Sultan’ or ‘Caliph’ who resided in the capital, also named Sokoto, the empire was made up of several emirates, which were quasi-vassal political units built on top of pre-existing Hausa institutions, such as the emirates of Kano, Katsina, Zaria, and Adamawa.

The vast size of the Caliphate erased pre-existing political barriers, which created a large internal market and influenced major demographic changes that facilitated the expansion of the region's economy. The rapid growth of textile manufacturing in the empire emerged within this context, bringing together various textile traditions in an efficient distribution network that included a greater share of the ordinary population than was possible in the preceding period1.

The material basis of Sokoto's economy was provided by the political and ideological control of land through a state dominated by an officeholding class. In a society where the majority of producers maintained possession of land and experienced a low level of economic subsumption, surpluses were primarily accrued through rents. That is ‘a politically based exaction for the right to cultivate… whose level will depend upon the coercive means available through the State’. This resulted in the creation of a ‘mixed economy’ where the State played a central role in economic production and regulating institutions, albeit only as one among many different economic agents.2

The economic policies adopted by Usman's successors served to consolidate the territories acquired during the movement as well as to restore and integrate their economies. Most of these policies were undertaken by Muhammad Bello who is credited with establishing ribats (garrison towns) in peripheral regions, eg between Kano and Adamawa, that were settled by skilled artisans and merchants who developed local economies, and urbanized the hinterlands.

Bello's writings to his emirs include instructions to

"foster the artisans, and be concerned with tradesmen who are indispensable to the people, such as farmers and smiths, tailors and dyers, physicians and grocers, butchers and carpenters and all sorts of traders who contribute to [stabilising] the proper order of this world. The ruler must allocate these tradesmen to every village and every locality."3

The urbanisation of rural areas, as well as the improved accessibility, allowed for greater administrative control through the appointment of officials (jakadu) who controled trade and collected taxes (on dye pits, hoes used in farming, and trade cloth).4 This influenced the activities of long-distance traders, farmers, and craftsmen, by reinvigorating pre-existing patterns of trade and population movements that had been initiated by the Hausa kingdoms centuries earlier to create numerous diasporic communities across West Africa.

The manufacture and trade of textiles in Hausaland predated the industry's expansion in the 19th century.

The earliest written accounts describing the Hausaland region in the 14th century mention the presence of Wangara merchants (from medieval Mali), who settled in its cities and wore sewn garments. These Wangara merchants also appear in earlier accounts from the 12th century, when they are described as wearing chemises and mantles. They were thus likely involved in the development of the Hausa textile and leather industry, which would receive further impetus from the westward shift of the Bornu empire in the 15th century, which also possessed a thriving textile industry and used cloth strips as currency.5

By the 16th century, local textile industries had emerged across Hausaland, especially in the cities of Kano, Zamfara, and Gobir. According to Leo Africanus' account, grain and cotton were cultivated in large quantities in the Kano countryside and Kano's cloth was bought by Tuareg traders from then north. Other contemporary accounts mention the arrival of Kanuri artisans from Bornu, the trade in dyed cloth from Kano, as well as the import of foreign cloth from the Maghreb. After the 17th century, the white gown (riga fari) became popular among the ordinary population, while the elites wore the large gown (babbar riga), which in later periods would be adopted by the former.6

This pre-existing textile industry and trade continued to expand over the centuries and would grow exponentially during the 19th century.

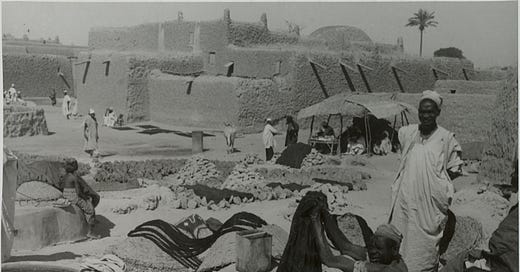

Kano in 1931, Walter Mittelholzer.

Cotton cultivation in the Sokoto empire.

Most of the cloth produced in Hausaland was made from cotton and silk, which was cultivated locally by farmers together with their staple crops. Cotton cultivation, which had been undertaken in the region for centuries, is however, highly sensitive to rainfall, requires significant land and labour, and is subject to price fluctuations caused by taxation and market speculation, all of which could result in hefty economic losses for a farmer if not carefully managed7.

Initially, the emirates of Zaria and Zamfara specialized in growing cotton while those of Sokoto and Kano specialized in manufacturing textiles. This would gradually change by the late 19th century, as textile manufacturing expanded rapidly across most emirates and the demand for raw cotton was so high that considerable quantities of yarn were even imported from Tripoli.8

Embroidered cotton gown (shabka) made in Zaria, Nigeria. ca. 1950. British Museum.

The comparative advantage of Zaria and Zamfara in cotton growing was enabled by its middle-density population, its clayey soil rich in nitrates, and the relative abundance of land for swidden agriculture. Besides the pre-existing population of farmers who grew their own cotton on a small scale, large agricultural estates were also established by wealthy elites and were populated with clients and slaves, the latter of whom were war captives or purchased from the peripheral regions9.

The explorer Hugh Clapperton, who visited Sokoto in 1826 and provides some of the most detailed descriptions of its society, including on slavery, writes: “The domestic slaves are generally well treated. The males who have arrived at the age of eighteen or nineteen are given a wife, and sent to live at their villages and farms in the country, where they build a hut, and until the harvest are fed by their owners. The hours of labour, for his master, are from daylight till mid-day; the remainder of the day is employed on his own. At the time of harvest, when they cut and tie up the grain, each slave gets a bundle of the different sorts of grain for himself. The grain on his own ground is entirely left for his own use, and he may dispose of it as he thinks proper. At the vacant seasons of the year he must attend to the calls of his master, whether to accompany him on a journey, or go to war, if so ordered.10”

This was repeated later by Heinrich Barth who visited Sokoto from 1851-1854, noting that “The quiet course of domestic slavery has very little to offend the mind of the traveller ; the slave is generally well treated , is not over worked , and is very often considered as a member of the family” but he differs slightly from Clapperton with regards to marriages among ‘slaves’, suggesting that they weren’t encouraged to marry, which he surmises was the cause of the institutions’ continuation.11

Scholarly debates on the nature of slavery in Sokoto, as in most discussions of ‘internal slavery’ in Africa, reveal the limitations of relying on conceptual frameworks derived from the historiography of slavery in the Americas 12 (this includes Clapperton and Barth’s quotes above, who refer to ‘slaves’ on agricultural estates as ‘domestic slaves’).

For the sake of brevity, it is instructive to use a comparative approach here to illustrate the differences between the ‘slaves’ in west Africa versus those in the Americas; the most important difference is the lack of a binary of ‘slaves’ and ‘free’ persons, as all social groups occupied a continuum of social relations from elites and kin-group members, to clients and pawns, to dependants and captives. Aside from the royals/ruling elites, none of these groups occupied a rigid hierarchy but instead derived their status from their relationship with other kin-groups or patrons, hence why slaves could be found on all levels of society from governors and scribes, to soldiers and merchants, to household concubines and plantation workers13.

Most ‘slaves’ in Sokoto could work on their own account through the murgu system thus accumulating wealth to establish their own families, gain their own dependants,and in some cases, earn their freedom. Still, their labor, social mobility, and rate of assimilation were negotiated by the needs of political authorities, making slavery in Sokoto a political institution as much as it was a social institution. This created highly heterogenous systems of slavery, with some powerful ‘slave-officials’ exercising authority over ‘free’ persons and ‘slaves,’ with some client farmers and ‘slaves’ working on the same estates owned by state officials, aristocrats or wealthy merchants, some of whom could also be ‘slaves’.14

Despite the complexities of ‘slavery’ in Sokoto, the significance of slave use in its textile industry and the economy was inflated in earlier scholarship according to more recent examination. The empire of Sokoto was a pre-industrial society, largely agrarian and rural. The bulk of economic production was undertaken by individual households on a subsistence basis, with the surplus produce (grain, crafts, labour, etc) being traded for other items in temporary markets, or remitted as tribute/tax to authorities whose capacity for coercion was significantly less than that of modern states, and whose economy was ultimately less influenced by demand from international trade.15

It’s for this reason that while 'slaves' would have been involved in the cultivation process alongside 'free' workers who constituted the bulk of the empire’s population, ‘slaves’ were less involved in the textile manufacturing process itself which required specialized skills, and was considered respectable for ‘freeborn’ persons including the scholarly elite.16

The political economic and ideological tendency in the empire was mainly toward the production of peasants who could be taxed, as well as in their participation in the regional economy where more rents could be extracted.17 Additionally, the textile industry also relied on the mobility of 'free' labour, including not just ordinary subjects, but also skilled craftsmen and traders from among the Tuareg, Kanuri, Fulani, Nupe, and Gobir. These were involved in all stages of cloth production from spinning to dyeing, they became acculturated into the predominantly Hausa society and settled in the major textile centers18.

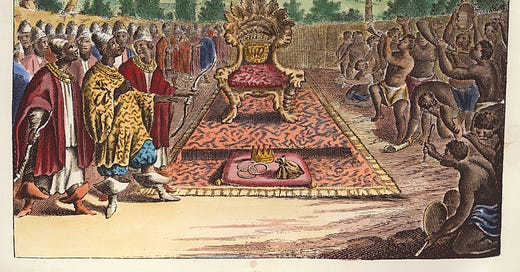

'Robe and cap of the King of Dahomey given to Vice-Admiral Eardley Wilmot,’ ca. 1863-1866. British Museum. Art historian Alisa LaGamma suggests that this robe, which was part of a diplomatic gift from Dahomey (in modern Benin) to Britain, ultimately came from the Sokoto empire and was likely made by Nupe and Hausa weavers and embroiderers.

The textile production process.

The manufacture of textiles was not just the prerogative of a few specialized artisans but involved the bulk of the population in both urban and rural areas. While clothing was a symbol of religious and social identity, its manufacture and exchange in Hausaland was the expression of a culture that tended to integrate different strata of the population regardless of social identity.19

The empire's textile industry underwent significant changes over the course of the 19th century, especially in major centers like Kano where specialization increased as different cities and towns took over specific parts of the production processes, resulting in significant economies of scale. Increased demand and competition led to a rapid improvement in standards of workmanship and the quality of cloth produced. This in turn, created an internal market for highly skilled labour whose training period could last as long as 6 years.20

Textile workers differed in the kinds and levels of skills attained, the types of products they made, and the stage in the process: the garments changed hands at different stages in the process of spinning, weaving, sewing, beating and dyeing. The empire's diverse textile industry combined two pre-existing production systems; one north of the Niger-Benue region where most spinners were women, while men did the weaving, dyeing, and embroidering; and one south of the Niger-Benue region where both women and men were involved in all processes.21

Talismanic cotton tunic (riga) made by a hausa weaver in northern Nigeria, late 19th century, British museum.

Cotton and silk robe embroidered with checkered patterns and the 8-knife motif. late 19th century, British Museum.

Spinning was the slowest and most laborious activity in the process, it was done in domestic settings often by women who were supplied with local cotton and silk as well as imported yarn from the Maghreb. On the other hand, weaving was undertaken by the greater part of the population as a secondary occupation when farming activities were suspended. Weavers, both men, and women, used a transportable horizontal double-heddle loom as well as a vertical loom to produce narrow strips of cloth which were later sewn together.22

The two main subgroups of looms used in Hausaland were defined by two ranges of standard cloth width, indicating two types of production in the export sector: cloth consisting of very narrow strips (1.25–6 cm) was transported in the salt and natron trade to Bornu and Air, whereas wider strips (8–12 cm) were prominent in trade to the western Sudan region. The latter type of loom was likely associated with the rise of the kola trade to Gonja in the late 18th century, but would have existed in the Gonja region centuries earlier.23

In cities like Kano, local weavers were at times joined by skilled immigrants from the Bornu empire and the Nupe region, with many diverse groups contributing to the production of luxury and ordinary cloth as the garments changed hands multiple times. Craftsmen often had no special workshops but instead worked in or near the markets according to local demand, although specialist quarters like the Soron D’Inki ward of Kano were developed by skilled tailors and dyers.24

Man's gown composed of 250 narrow strips of hand-spun and hand-woven cotton, hand-sewn together along the selvage and thee ‘two knives’ embroidered design. early 20th cent. Nigeria. British Museum.

Trousers (Wando), 19th–20th century, Nigeria. Met Museum, Han Museum of Art.

The co-current expansion of domestic and external demand for dyed textiles stimulated the production of dyed textiles and the construction of dyeing pits. From 1815, outside the city boundaries of Sokoto, around 285 dyeing pits were built, while Kano in 1855 had more than 2,000 dyeing pits, which would increase to between 15,000 to 20,000 by the end of the 19th century with a corresponding number of dyers.25

Cloth-dyeing in Kano was a centuries-old practice that pre-existed the establishment of Sokoto. Dyers used huge fired-clay pots (Kwatanniya), that were waterproofed by burying them in beds of dyebath residue (katsi) and then lining them with laso cement (made from burned indo-dye residue mixed with viscous vegetable matter). By the 19th century, dyers in Kano, Sokoto, Katsina, and Zaria created much larger dyeing vats of laso cement, which reduced the unit cost of finished cloth.26

dyeing textiles with indigo in Kano, ca. 1938. Quai Branly.

Cloth dyers in Kano, ca. 1938, Quai Branly.

Dyers used locally cultivated indigo dye (Indigofera) and utilized specific methods to prepare the indigo dye vat. Like all parts of the textile manufacturing process, cloth dyeing was influenced by the activities of traders who took cloth strips from one textile center to another for stitching, dyeing, and embroidering. In the case of Kano, the town of Kura, about 20 miles to its south, was one of the city's major dyeing centers by the time of Barth's visit in 1851. In 1909, an estimated 2,000 dyers resided in the town out of a population of 8,000, and it was renowned for producing some of the finest and most expensive indigo-dyed cloths in Kano27.

Skillfully tailored and embroidered garments were the most expensive textile products made in the empire, and they were worn and distributed as gifts by the elite. Tailors and embroiderers used small needles to work specialized cloth that was designed particularly for the tailoring process. They were embellished with geometric designs and motifs drawn from a Muslim visual vocabulary that was international in scope and comprehensible to individuals in different strata of society.28

Cities like Sokoto initially specialized in producing white cloth (riga fari) because it was the religious center of Dan Fodio's movement with strict attitudes against the embellishment of clothes. But in other cities such as Kano, and in most emirates during the later periods, more embellished garments such as the rigan giwan, a robe embroidered with eight-knife imagery, became very important among the elites and wealthy.29

Cotton Robe with the 8-knife motif, and embroidered trousers with interlace patterns, early 20th cent, British museum. These were worn together with a long-sleeved shirt.

woman's cotton robe embroidered in purple, green, and yellow silk thread in geometric patterns. ca. 1920-1935, British Museum.

cotton robe with silk embroidery, made in Ilorin, Nigeria ca. 1875, Art Institute of Chicago

The textile trade in the 19th century Hausalands: proto-industries, merchants, and the state.

The expansion of domestic demand and the emergence of new markets opened new avenues for the accumulation of wealth, especially among traders and artisans from the larger cities who moved to more peripheral regions to compensate for the increasing taxes, or to benefit from colluding with established authorities.30

During the 19th century, Kano’s textile industry reached extraordinary production levels. In 1851 the city of sixty-thousand produced an estimated 300 million cowries worth of textiles ( which was £30,000 then or £5,2m today), with atleast 60 million cowries worth of textiles being exported to Timbuktu. At a time when Barth noted that a family in Kano could live off 50-60,000 cowries a year "with ease, including every expense, even that of their clothing", he also mentions that one of the more popular dyed robes cost 2,500-3,000 cowries. He notes that Kano cloth was sold “as far as Murzuk, Ghat, and even Tripoli; to the west, not only to Timbucktu, but in some degree even as far as the shores of the Atlantic, the very inhabitants of Arguin (in Mauritania) dressing in the cloth woven and dyed in Kano”.31

Kano’s popularity as a market was due to a series of commercial incentives and the greater regulation of market transactions. As reported by Clapperton, the Kano market was regulated with great fairness; if a garment purchased in Kano was discovered to be of inferior quality it was sent back, and the seller was obliged to refund the purchase money.32

The demand for Kano textiles throughout this vast region persisted after Barth’s visit. Writing in 1896, Charles Henry Robinson, who visited the city of Kano and estimated that its population had grown to about 100,000, mentions that, “it would be well within the mark to say that Kano clothes more than half the population of the central Sudan, and any European traveler who will take the trouble to ask for it, will find no difficulty in purchasing Kano-made cloth at towns on the coast as widely separated from one another as Alexandria, Tripoli, Tunis or Lagos.”33 Similar contemporary accounts stress that consumers made fine distinctions between cloths on the basis of quality which contributed to the tremendous range in price for what appeared to be similar textiles.34

Local and imported textiles became one of the main items used as a store of wealth in the empire’s public treasury at the city of Sokoto and constituted a considerable part of the annual tribute pouring in from the other emirates to the capital. Kano, for example, sent to Sokoto a tribute of 15,000 garments per year in the second half of the 19th century.35

Many rich merchants (attajiraj) settled across the empire’s main cities and exported textiles to distant areas where they at times extended credit to smaller traders. Merchant managers were able to achieve economies of scale by storing undyed cloth in bulk and by establishing large indigo dyeing centers, some showing features of a factory system, with itinerant cloth dyers hired to work for wages. The capital for these enterprises came from the high-profit margins of long-distance trade, with large land and labor holdings acquired through political and military service36.

The traders in the finished products and the landlords (fatoma) frequently accommodated visiting buyers and arranged sales. In the second half of the 19th century, these rich merchants began to acquire greater influence in Kano business circles. The power of these merchants was such that when the price of textiles fell, the merchants were able to buy most of them and wait for prices to rise again37.

Some of the wealthiest merchants created complex manufacturing enterprises dealing with the import and export trade across long distances by controlling a significant proportion of the production process. They acquired large agricultural estates, expanded labour (which included kinsmen, 'free' workers, and clients as well as 'slaves'), and established agents in distant markets abroad.

One such trader in the 1850s was Tulu Babba, whose Kano-based enterprise operated across four emirates. It consisted of; a family estate and 15 private estates worked by kinsmen, clients, and ‘slaves’; several contracted dyers and master tailors in Kano; and a factor agent in Gonja. Medium-sized enterprises run by wealthy women merchants also utilized the same form or organization, with family estates where the entire household was involved in the manufacturing process, and their labour was supplemented by client relationships formed with 'female-husbands' whose households were also involved in the spinning and weaving processes.38

Manufacturing of indigo in Kano. ca. 1938, Quai Branly. The entire household would have been involved in the production process.

Man’s gown (riga), acquired in the Asante kingdom (modern Ghana), ca. 1887-1891. British Museum. The collector called it an “extremely handsome garment” and ‘the characteristic garment of the Mohammedan men”. Hausa traders were the main Muslim merchants in 19th-century Asante, from the town of Salaga in Gonja to the coastal regions.

Other merchants oversaw more modest operations that were nevertheless as significant to the textile economy as the larger enterprises, while also involving many other commodities according to circumstance.

One such trader was Madugu Mohamman Mai Gashin Baƙi, a carravan leader who was born in Kano in the late 1820s, and undertook his first trip to Ledde in the Nupe kingdom when he was 16, where they “sold horses to the king in exchange for Nupe cloth”, and returned to Kano after six months. The caravan then traveled to Adamawa region, where they purchased ivory on a second trip, while on a third trip, he went to the Bauchi area and then on to Kuka (the capital of Adamawa at that time), where he bought galena (a mineral used for eye makeup), which he took back to Kuka. He then returned to Bauchi with five large oxen that he had purchased and had loaded with natron, which he subsequently sold39.

This level of trade likely represented the bulk of the textile trade across the empire, with small caravans of Hausa traders traveling in the dry season using donkeys to bring goods from Kano and other cities that they could trade along the way, exchanging cloth for other commodities in places as far as Fumban (capital of Bamum kingdom in Cameroon) and the Asante capital Kumasi in ghana.40

Cotton trousers embroidered with patterns of diamonds, stripes, knots, circles, and yellow in herringbone stitch. Hausa tailor, acquired in Cameron, ca. 1920, British Museum. The Hausa and other groups associated with Sokoto expanded their activities to Cameroon during the second half of the 19th century, trading cloth and proselytizing as far as the Bamum kingdom.

Hausa riga from modern Benin, collected in 1899, Quai Branly.

Hausa musician in Fumban, Hausa teacher in Fumban ( c. 1911, 1943, Basel Mission Archives)

Wealthy merchants benefited from the city authorities of Kano who facilitated the export of textiles from this city to distant areas like Adamawa. Unlike North African traders who were forced to pay taxes on their commercial transactions, the rich local merchants accumulated enough wealth and influence to monopolize most of the empire's long-distance trade alongside middlemen located in distant areas like Lagos, who increasingly demanded higher percentages of commercial transactions41.

The monopoly on trade by these merchants and the increase in taxes on all commerce shows that the Empire's politics became more oligarchic in the late 19th century, with authorities drawing their legitimacy more from the wealthy elites and less from the common population. This collusion between rulers and traders likely contributed to the empire's political fragmentation, among other factors, as each emirate increasingly became autonomous and could thus offer no significant resistance before it fell to the British in 1903.42

Despite the disruption of the early colonial period, the textile industry of the Hauslands continued to flourish well into the middle of the 20th century when a combination of competition from cheaper, machine-made imports, reorganisation of labour, and changes in policies, contributed to its gradual decline. Cloth dyeing and hand-woven textiles still represent a significant economic activity in the Hausalands in the modern day, with cities like Kano preserving the remnants of this old industry.

A view of a section of the 500 years old Kofar Mata dye pits in Kano.

The 19th century world explorer Muhammed Ali ben Said of Bornu, traveled across over twenty countries in the four continents from 1849 to 1860 before serving in the Union Army during the American civil war and settling in the US where he published his travel account.

Please subscribe to Patreon to read about Said’s fascinating journey across Europe, western Asia and the Carribean, here;

Big Is Sometimes Best: The Sokoto Caliphate and Economic Advantages of Size in the Textile Industry by Philip J. Shea pg 5-7)

Silent Violence: Food, Famine, and Peasantry in Northern Nigeria By Michael J. Watts pg 78-81.

Veils, Turbans, and Islamic Reform in Northern Nigeria By Elisha P. Renne pg 30-32

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 196-199, 204-205)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 188-191)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 192-194)

Cotton Growing and Textile Production in Northern Nigeria from Caliphate to Protectorate c. 1804-1914’: A Preliminary Examination by Marisa Candotti pg 4)

Cotton Growing and Textile Production in Northern Nigeria from Caliphate to Protectorate c. 1804-1914’: A Preliminary Examination by Marisa Candotti pg 5)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 196-197)

Journal of a second expedition into the interior of Africa, from the Bight of Benin to Soccatoo. By. Clapperton, Hugh

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa Volume 1 By Heinrich Barth

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff pg 77-78.

Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives by Suzanne Miers and Igor Kopytoff pg 15-39, 45-47.

Plantation Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate: A Historical and Comparative Study By Mohammed Bashir Salau pg 47-90, Jihād in West Africa During the Age of Revolutions by Paul E. Lovejoy.

Silent Violence: Food, Famine, and Peasantry in Northern Nigeria By Michael J. Watts pg 60-77.

Big Is Sometimes Best: The Sokoto Caliphate and Economic Advantages of Size in the Textile Industry by Philip J. Shea pg 13-14)

Silent Violence: Food, Famine, and Peasantry in Northern Nigeria By Michael J. Watts pg 77-78)

Big Is Sometimes Best: The Sokoto Caliphate and Economic Advantages of Size in the Textile Industry by Philip J. Shea pg 15)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 187)

Cotton Growing and Textile Production in Northern Nigeria from Caliphate to Protectorate c. 1804-1914’ by Marisa Candotti pg 6, Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 375-376.)

Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 368-372, Cotton Growing and Textile Production in Northern Nigeria from Caliphate to Protectorate c. 1804-1914’ by Marisa Candotti pg 5

Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 377-385

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 195)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 202)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 200, Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 391)

Big Is Sometimes Best: The Sokoto Caliphate and Economic Advantages of Size in the Textile Industry by Philip J. Shea pg 7-9)

Big Is Sometimes Best: The Sokoto Caliphate and Economic Advantages of Size in the Textile Industry by Philip J. Shea pg 9-12, Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 387-389)

Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 389-391)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 200)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 205)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being a Journal of an Expedition Undertaken Under the Auspices of H. B. M.'s Government, in the Years 1849-1855, Volume 1 by Heinrich Barth.

Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa by D.Denham and H. Clapperton, 653

Hausaland Or Fifteen Hundred Miles Through the Central Soudan by Charles Henry Robinson pg 113

Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 365)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 201)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land , Economy , and Society of His People by Douglas Edwin Ferguson, 374–8, Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 391)

Cotton Growing and Textile Production in Northern Nigeria from Caliphate to Protectorate c. 1804-1914’ by Marisa Candotti pg 6)

Textile Production and Gender in the Sokoto Caliphate by Colleen Kriger pg 392-396)

Veils, Turbans, and Islamic Reform in Northern Nigeria By Elisha P. Renne pg 32-35

African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon edited by Ian Fowler, David Zeitlyn pg 176-178, From Slave Trade to 'Legitimate' Commerce edited by Robin Law pg 97-98

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 204)

Being and Becoming Hausa: Interdisciplinary Perspectives edited by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 205-206)