A complete history of Dogon country: Bandiagara from 1900BC to 1900AD

demystifying an ancient African society

Rising above a the semi-arid plains of central Mali, the dramatic landscape of Bandiagara with jagged escarpments and sandy plateaus is home to some of Africa's most fascinating societies.

The Dogon population of Bandiagara are arguably the most studied groups in African anthropology. But the history of the Bandiagara region is relatively poorly understood, it often relies on outdated concepts, and occasionally employs essentialist theories in describing the region's relationship with west African empires.

Recent research on the Bandigara's history has revealed that the region was central to the political history of west African empires. Bandiagara was often under imperial administration and was integrated into the broader systems of cultural and population exchanges in west Africa. Rather than existing in perpetual antagonism with the expansionist empires, the population of Bandiagara employed diverse political strategies both as allies and opponents.

The recent studies have shown that Bandiagara wasn't an impermeable frontier and its Dogon population weren't a homogeneous group living in isolation; these fallacies emanate from external imaginary than from local realities.

This article outlines the complete history of Bandiagara since the emergence of the region's earliest complex societies. It examines the political history of Bandiagara under various empires, as well as the social institutions of the Dogon.

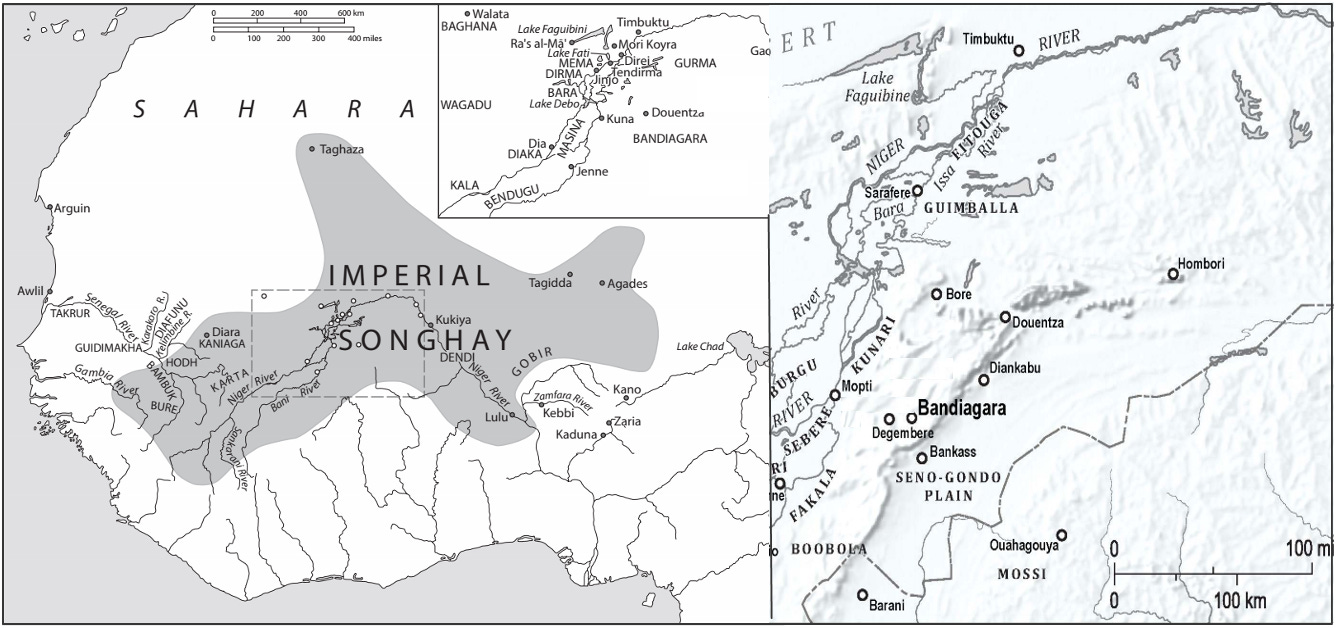

Map showing the location of the Bandiagara region 1

If you like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

The emergence of complex societies in Bandiagara: 1900BC-1100AD

The region of Bandiagara is composed of three zones : the plateau, the escarpment and the lower plains. The plateau rises to a height of approximately 300 meters above surrounding plains and is delimited by the Bandiagara escarpment —a row of sandstone cliffs that rise about 500m and extend 150km from the southwest to the northwest— while the plains of the Seno-Gondo lie to the southeast, just below the cliffs.

The emergence of complex societies in the region begun around the early 2nd millennium BC with the establishment of small agricultural settlements on the Bandiagara plateau and in the Seno Plain. The construction of stone houses and the growing of pearl millet was well established at sites like Ounjougou on the plateau by 1900-1800 BC2. This first phase of settlement in Bandiagara was succeeded by a period of population decline between 400BC-300AD during which time the region's population was mostly confined to the escarpment at sites such as Pégué cave A3.

The population of Bandiagara later recovered around the 4th century AD, with multiple iron-age sites growing into large networks of agro-pastoral villages that were established on the plateau, in the escarpment and on the plains. These settlements include the plateau site of Kokolo, the escarpment site of Dourou Boro, and the Seno plain sites of; Damassogou, Nin-Bèrè, Ambéré-Dougon, and Sadia all of which occupied from the late 1st millennium BC to early 2nd millennium AD. These sites were linked to regional and long distance routes across west African as evidenced by the discovery of glass beads and other trade items at Dourou Boro and Sadia.4

The Seno plain site of Sadia settled from 700-1300, constituted a complex village network connected to the emerging urban trade centers such as Jenne. Sadia and other settlements in the Bandiagara region were contemporaneous with the southward movements of the Neolithic populations from the ancient sites of Dhar Tichitt and the inland Niger delta between Mema to Jenne-jeno. These early developments were also associated with the emergence of the Ghana empire.5

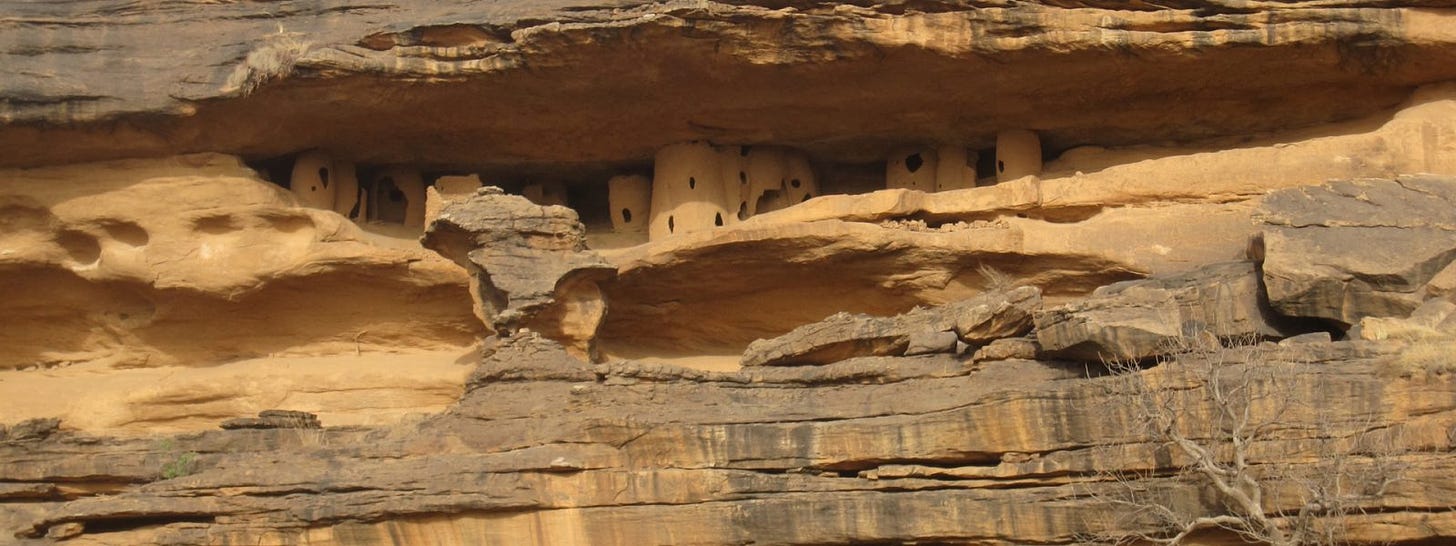

"Toloy" cave within the escarpment. "Toloy" site of Pégué cave A, showing the coiled-clay buildings6

Medieval Bandiagara: demystifying then “Tellem” to “Dogon” sequence.

The little that is known about the early societies in the Bandiagara region (prior to the medieval empires of Mali and Songhai) is based on the material culture of the region's archeological sites as well as oral traditions recorded in the last century. While some of the different phases of occupation outlined above were once thought to correspond to different groups of people; labeled; "Toloy" (200BC-300BC), "Tellem" (1100-1500AD) and "Dogon"(1600-present), this population sequence has since been revised, especially since the sites of Bandiagara show an unbroken continuity in settlement, and a cultural continuity in burial practices. The terms; "Toloy", "Tellem" and "Dogon" therefore don't correspond to distinct cultural groups, but are now simply used as a way of organizing historical information about Bandiagara into a unitary scheme.7

The population that flourished in the Bandiagara region during the early 2nd millennium lived in complex societies sustained by a vibrant agro-pastoral economy as well as metallurgy, cloth making, leatherworking, wood carving and pottery. They spoke an incredibly diverse range of languages belonging to both the Nilo-saharan and Niger-congo families related to the neighboring languages of Songhay (Nilo-saharan) and Mande (Niger-Congo), but also included language-isolates that remain unclassified.8

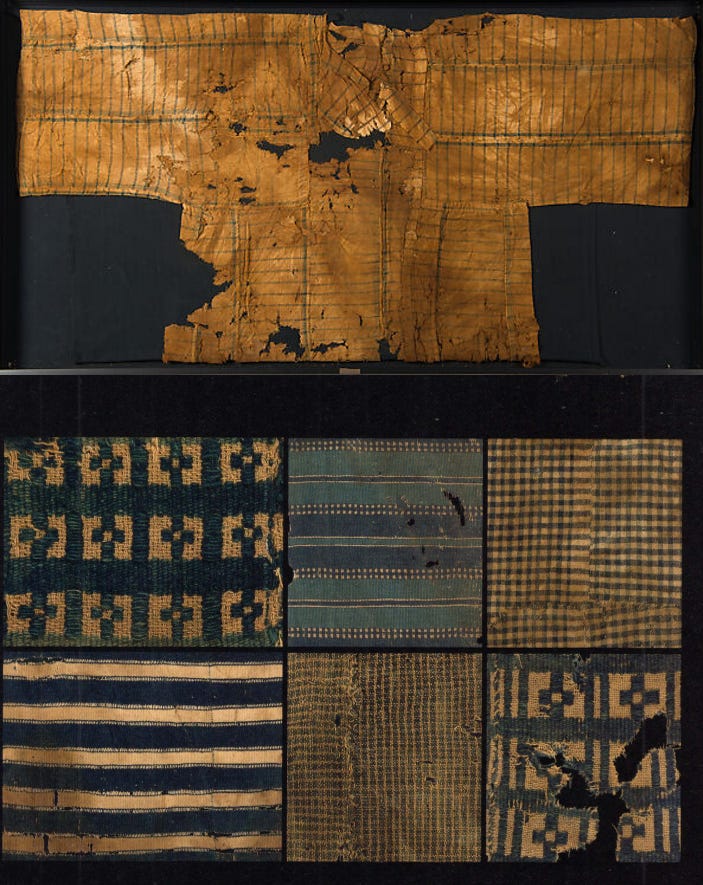

They constructed houses of stone and mudbrick and some of them buried their dead high up inside the caves of the escarpment. These burials were protected by small walls of hand-molded mud brick reinforced by wooden pillars, or by stone walls covered with clay. The individuals laid to rest within the Bandiagara caves were clothed and wrapped in dyed cotton and/or wool blankets. The large volume of cotton textiles deposited in these burials and the homogeneity of their weaving technique, decoration, and format evidence of an indigenous weaving industry.9

Among the different forms of apparel were a variety of caps, women's wraps, and male tunics with wide sleeves and blankets. They were made by sewing together narrow strips of cotton cloth using the typical West African horizontal looms10. Other grave goods include leather aprons, sandals, bags, and knife sheaths; adornments such as cylindrical quartz plugs and beads made of glass, and gemstones; as well as weapons and wood carvings.11

“Tellem” houses inside the cliff face of Bandiagara. Tellem constructions at Yougo Dogorou12

Tunic and Textile fragments from the "Tellem", 11th-12th century, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, and Musée National du Mali, Bamako

Bandiagara within Imperial Mali and Songhai (13th-16th century): and the “arrival” of the Dogon.

The growth of large complex settlements within the Bandiagara region during the early 2nd millennium coincided with an era of expansion of Mande cavalry bands which created subordinate polities that paid tribute to the rulers of Mali. In other occasions, these horsemen established autonomous polities whose institutions were similar to those found in the Mali empire. Accompanying such elites were craftsmen such as leatherworkers, blacksmiths, wood carvers and others, who made products for domestic consumption as well as for regional and long distance trade.13

During the Songhai era, the mountainous Bandiagara region was controlled by officials in the Songhai administration with the title of 'Tondi-farma', and Hombori-koi. The region appears as "al-jibal" (Arabic word for the mountains) or as "tondi" (Songhay word for the rock) in the 17th century Timbuktu chronicles. According to these chronicles, the populations of parts of Bandiagara were called 'Tunbula' (corresponding to Tombola; one of the ethnonyms of the Dogon). They are described as a "very large tribe (qabila) of the majus" (ie; non-Muslims who are tolerated within Muslim domains).14

Map showing the region of Bandiagara within the Songhai empire15

Most of Bandiagara appears to have been held relatively firmly during the entirety of the Songhai era, having been conquered early during Sunni Ali's reign around 1484, with the only other recorded campaign being that of Askiya Dawud in 1555 which was part of a wider series of pacification campaigns.16 Given its location near Songhai's frontier with the Mossi kingdom of Yatenga, there were significant interactions and population movements between the Bandiagara and Yatenga in the 16th and 17th century, especially since Yatenga was often a target of Songhai attacks. The exact dating and nature of the interaction between Yatenga and the Bandiagara region at this early stage is however rather obscure.17

The curious office of Tondi-farma appears only during Sunni Ali's reign and was likely created for his military official Muḥammad Ture during the course of the campaigns despite Ture's fraught relationship with Sunni Ali. Shortly after Sunni Ali's death in 1492, Muhammad Ture would depose the deceased ruler's son and seize the throne as Askiya Muhammad. Conversely, the office of Hombori-koi appears during the reign of; Askiya Ishaq (1539-1549) and Askiya Bani reign (1586-1588) and Askiya Ishaq II (1588-1592). It more likely includes the northernmost region of Bandiagara closet to the Niger river valley, especially around the town of Douentza.18

Oral traditions of the Dogon date their "arrival" in the Bandiagara region to during the height of imperial Songhai between the 15th-16th century. Most traditions often refer to the "pre-existing" population was called Tellem (we found them), but in other traditions, the pre-existing population is referred to as Nongom who are claimed to be distinct from the Tellem but contemporaneous with them.19

Such traditions are difficult to interpret but more likely represent the arrival of groups of elites, craftsmen or small groups rather than the wholesale migrations of distinct ethnicities and displacements of pre-existing populations.20The present Dogon populations of the escarpment, plateau and Seno plain form a heterogeneous population whose movement spans several centuries and doesn't constitute a "bounded ethnic" group. The Dogon's internal ethnic diversity takes on many forms including a variety of languages, architecture and material culture.21

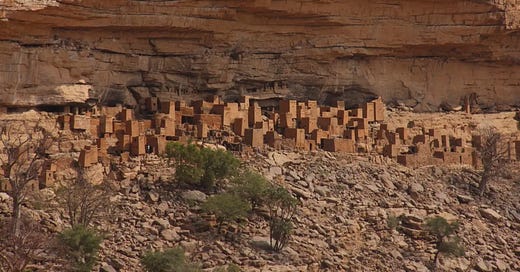

Banani village near the town of Sanga

Dogon villages in the escarpment overlooking the plain

Independent Bandiagara after Songhai: examining Dogon political and social institutions.

The collapse of Songhai in 1591 dramatically reshaped the political landscape of west Africa and the Bandiagara region as well. The Moroccan garrisons at Timbuktu, Gao and Jenne could barely control the cities, and had no authority in the countryside. An expedition by the Pasha Mahmud in 1595 briefly captured parts of Bandiagara (identified as al-Hajar, Hombori and Da'anka) but hi camp was ambushed by the local archers and he was killed; his head was sent to the Askiya Nuh exiled in Dendi. Besides one mention of an expedition into the northern regions of Bandiagara by Pasha Hamid in 1647, there was no attempt by the Moroccans to take any part of the region.22

Map showing the Bandiagara region including some of the main Dogon settlements23

It's during this period in the 17th and 18th century that most of the political and social institutions of the Dogon would have fully emerged. Dogon society was controlled by loosely united chiefdoms or federations that are comprised of clans, lineage and villages. These 'federations' are often referred to as "tribes" which constituted closely related lineage groups (clans), they include the tribes of Dyon, Arou, Ono, Domno and Kor. The first four tribes share an elaborate tradition of cosmology and are distinguished in particular by the village from which they dispersed: with the Arou in the escarpment, the Ono and the Domno on the plains and the Dyon in the plateau.24

In the decentralized power structure of the Dogon, political and religious authority is shared between the hogon (chief of a 'tribe'), the priests and head of lineages, as well as the elders from each extended household. The hogon, the priests and the village elders share ritual responsibilities, their political authority being legitimized by their religious roles. The office is of the hogon is today mostly religious in nature but likely held considerable political influence in the past, especially since the hogon of Arou in particular is said to have maintained diplomatic relationship with the Yatenga kingdom25

The different Dogon settlements in the Bandiagara region and their distinct historical and geographic origins reveal the diversity of Dogon society. For example, the settlement at Niongono is occupied by the lineages of Degoga and Karambe which claim a Mande origin from the region of Segu before their purported arrival in the 15th-17th century. But the village itself was likely settled as early as the 12th century considering the dating of its earliest sculptures.26

Additionally, the settlement at Kargue was founded by the Janage lineage, which speak a dialect of the Bozo language. They claim an origin in the region of Jenne as part of a larger group called the Saman that reportedly arrived 15th/16th century. These settled on the plateau and initiated matrimonial political alliances with pre-existing elites. Their attempts at creating a political hegemony through alliances with the 19th century empires of Masina and Tukulor created distinct 'Saman' and 'Dogon' identities.27

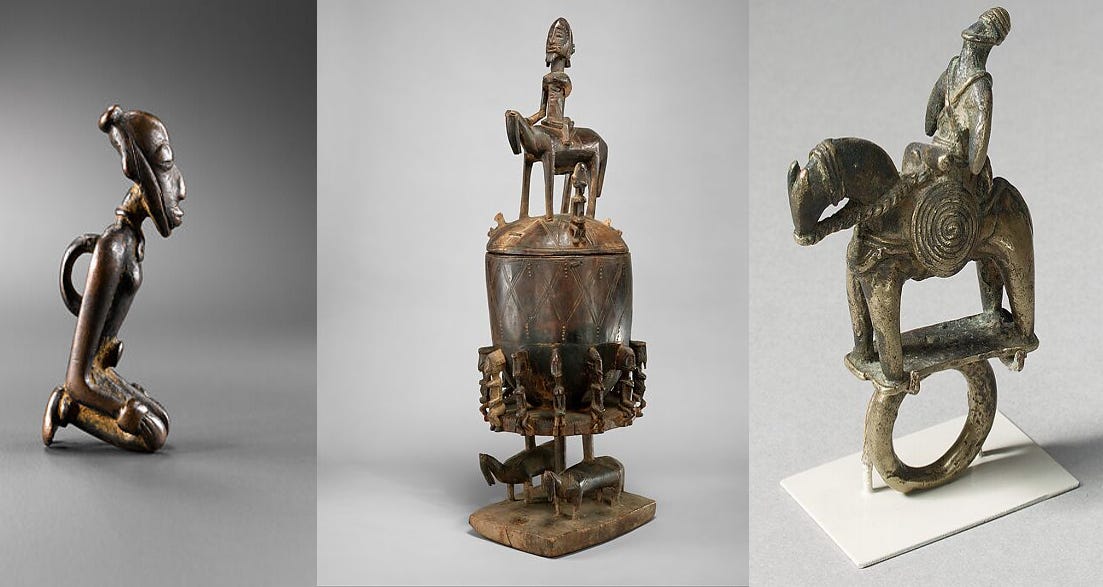

Dogon craftsmen created some of west africa's most recognizable art traditions using copper alloys, iron and wood to make a wide variety of artifacts. While the related activities of metallurgy and wood carving pre-dated the Dogon era, the emergence of an endogamous caste of blacksmiths occurred relatively late28. The blacksmiths rely on the patronage of wealthy clients to make artifacts, the priests then use the statuettes in religious activities, while individuals may use them for protection purposes.29

Bronze figure of a kneeling Male, 16th–19th century, private collection; Wooden Lidded vessel with an equestrian Figure, 1979.206.173a–c, met museum, Brass Ring with equestrian figure, 19th–20th century, 1981.425.1, met museum

There are four main traditional Dogon cults. These include; the Lebe cult related to fertility of the land, and its spiritual chief is the Hogon. There's the wagem cult which is an ancestral cult of an extended family and is presided over by the family head. There's the Binu cult which is concerned with maintaining harmony between the human settlements and the wild, and its headed by the Binu priest. Lastly is the society of masks which directs public rites that enable the transfer of souls of the deceased to the afterlife.30

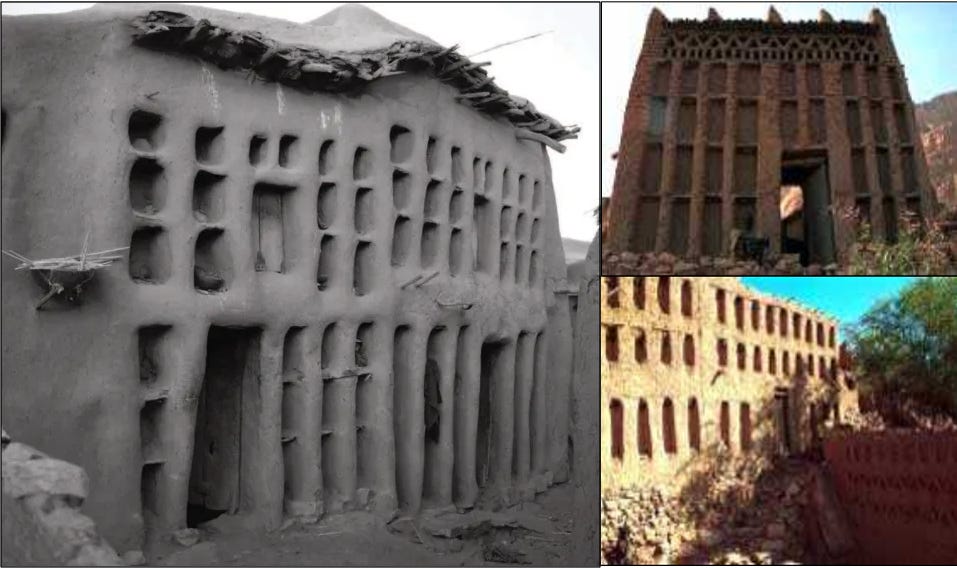

Dogon architecture displays a variation of the broader construction styles in the Niger river valley from Jenne to Timbuktu, but includes features that are unique to the Bandiagara region. Particular emphasis is placed on the façades which are often composed of niches with checkerboard patterns, the walls buttressed by pilasters leading upto flat roofs surmounted by multiple rounded pinnacles. The elder of an extended family lives in a large house (ginna) that is surrounded by the house of family members. The ginna is a two storied building with a façade showing rows of superimposed niches, while the the ancestor altar (Wagem) is in a sheltered structure that leads onto the roof terrace surmounted by ritual bowls.31

Sections of the Dogon had adopted Islam beginning around the 14th century, based on the estimated dating of the oldest mosque constructed in the village of Nando32. Built with stone, mudbrick and timber, the mosque's unique architecture —featuring pilasters on its façade and a roof terrace surmounted by conical pilasters— is a blend of architectural styles from Jenne and Bandiagara. Another mosque of about the same age as Nando was built at Makou, and is also said to be contemporaneous with the Nando mosque. Most of the Dogon mosques are of relatively recent construction beginning in the 19th century, and reproduce the same architectural features of domestic Dogon constructions.33

House of the Hogon of Arou

Façade of different ginna houses in Sanga

Nando Mosque

Bandiagara under the empires of Segu, Masina and Tukulor from 1780-1888

From the late 18th century, parts of the Bandiagara region were subsumed into the three successive empires which controlled the Niger river valley. The Bambara-led empire of Segu expanded over parts of the Bandiagara region, which comprised part of a shared frontier with the kingdom of Yatenga, and some wars were fought in its vicinity prior to the collapse of Segu to the Fulbe-led empire of Masina in 1818. During the early 19th century, the region of Kunari (adjacent to the plateau) was ruled by a Fulbe nobility of the Dikko and Sidibe under the Segu empire, and it was one of the first regions to be subsumed by the Masina forces led by Amhadu Lobbo.34

The Masina state then extended its control over most of Bandiagara plateau (known as Hayre in Masina documents). The Masinanke (the elite of Masina) appointed a provincial ruler (Amir) named Gouro Malado who goverened most of the plateau, and below him are subordinate chiefs who were in charge of local politics. In the northern sections of the plateau, the villages of Ibissa, Samari and Dagani put themselves under the protection of the chief de Boré, who also a vassal of Masina. Around 1830, most of the Seno plains of Dogon country were annexed by the armies of Ahmadu Lobbo's successor; Ba Lobbo after quelling a major armed movement by the Dogon of Seno against Masina expansionism. Sections of the Dogon that were residing in the Séno plain and were opposed to Masina, abandoned the plain and moved to the escarpments.35

The seno plain was however not firmly controlled and remained a semi-autonomous zone where rebellious Fulbe elites opposed to the Masina state could settle. Some of the Fulbe elites from Dikko founded the town of Diankabu in the Seno plain. Diankabu was led by Bokari Haman Dikko, a Masinanke noble who betrayed Ahmadu Lobbo and forged alliances with the Yatenga kingdom. However, the Dogon population of Diankabu occupied a subordinate position, as they did in most domains controlled by the Masina state.36

The northernmost regions of Bandiagara were also not fully integrated into the Masina state and remained under the control of small semi-autonomous polities such as the chiefdoms of Dalla and Booni. In these states, the relationship between the Fulbe elites, the Dogon and other groups was rather complex; with the Dogon of Booni occupying a relatively better position than those in Dalla.37

The empire of Masina was conquered by the Futanke forces of the Tukulor ruler El Hadj Umar Tal who captured the Masina capital of Hamdullahi in 1862. But the deposed forces of Masina regrouped and besieged their former capital from 1863-1864, forcing Umar Tal to make the pragmatic choice of sending his son Tijani Tal with a large quantity of gold inorder to ally with the Dogon of Bandiagara and provide him with mercenaries. But before Tijani would arrive with the Dogon relief force, the Futanke forces were forced out of Hamdullahi and Umar was killed shortly after in the region of Bandiagara where he had fled.38

Maximum extent of the Tukulor empire showing the Bandiagara region39

Following the death of Umar Tal in 1864, Tijani’s followers settled in the Bandigara region and established the capital of their new state at the eponymously named town of Bandiagara in 1868. Tijani forged alliances with Dogon at Bandiagara, especially on the plateau with the chiefs Sanande Sana and Sala Baji of Kambari. The strength of Tijani's coalition which included Dogon warriors allowed him to extend his influence over the rebellious Masinanke forces, who were captured and settled near the plateau, as well as against the Dogon in the Seno plain that were not part of the state. The Dogon forces of Tijani also secured his autonomy from the other half of the Tukulor empire centered Segu that was ruled by his brother Amadu Tal.40

Given its contested autonomy, the Bandiagara state ruled by Tijani was largely dependent on its military institution, which inturn rested on the diversity of his forces; among whom the Dogon were the most significant element. Tijani's alliance with the Dogon was secured through gift giving and sharing the spoils of war, with the Dogon chiefs being given top priory right after his own Futanke elites. The Bandiagara state wasn't a theocratic government like Masina since Its clerical elite did not hold power and its amirs didn't assume religious authority. The Dogon established a close political and social alliance with the Futanke elite, they shared domestic spaces, and their chiefs were treated with a level of respect.41

Tijani encouraged Islamic proselytization and mosque construction in Dogon settlements, but also allowed some non-Muslim Dogon religious and judicial practices to continue locally. Even at his capital, a Dogon court was overseen by the Dogon’s traditional Hogon priests, while Muslim law applied to the Futanke and other Muslim subjects. This was in stark contrast to the strict enforcement of theocratic law enforced by Tijani in Muslim settlements outside Bandiagara.42

Ningari mosque, ca. 1945, quai branly

Kargue mosque

kani kombole mosque

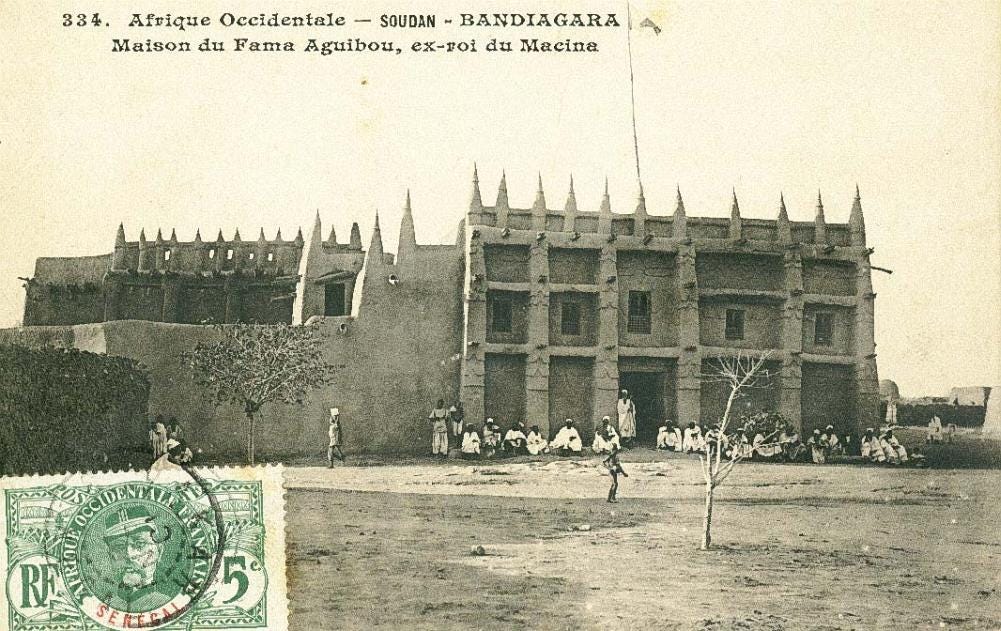

Bandiagara on the eve of colonialism

The Dogon featured prominently during the brief reign of Tijani's successor Muniru from 1887/8-1891. Muniru courted Dogon elites and mercenaries with gifts, and managed to seize control of Bandiagara by storming into the main mosque's grounds with his Dogon army while the Futanke elite were preparing for the Tabaski celebration. Muniru later rewarded his Dogon soldiers with a huge amount of cowries and cattle for installing him on the throne.43

Muniru's brief reign was a period of prosperity for the Bandiagara region and was remembered positively among the allied Dogon groups. But the arrival of the French armies which had colonized the other half of the Tukulor state at Segu in 1890, compelled Muniru to initiate diplomatic overtures to the French to retain a semblance of autonomy. This potential diplomatic alliance was however cut short when Ahmadu, the deposed Tukulor ruler of Segu fled to Bandiagara where he was welcomed by the elites. His tenure would be brief, and the French would in 1893 seize the capital Bandiagara with the assistance of Muniru's brother Agibu, who was then installed as the ruler.44

Unlike his predecessors, the relationship between the Dogon and Agibu was less cordial as the French forces gradually displaced the Dogon’s role as the guarantor of military power. While Agibu retained most of the Dogon fighting forces of his predecessors, the breakdown of the reciprocal gift giving system, the strong opposition from deposed Futanke elites, and a major rebellion in 1896, erased any semblance of state continuity. The region of Bandiagara formally became a French colony.45

Agibu’s palace at Bandiagara

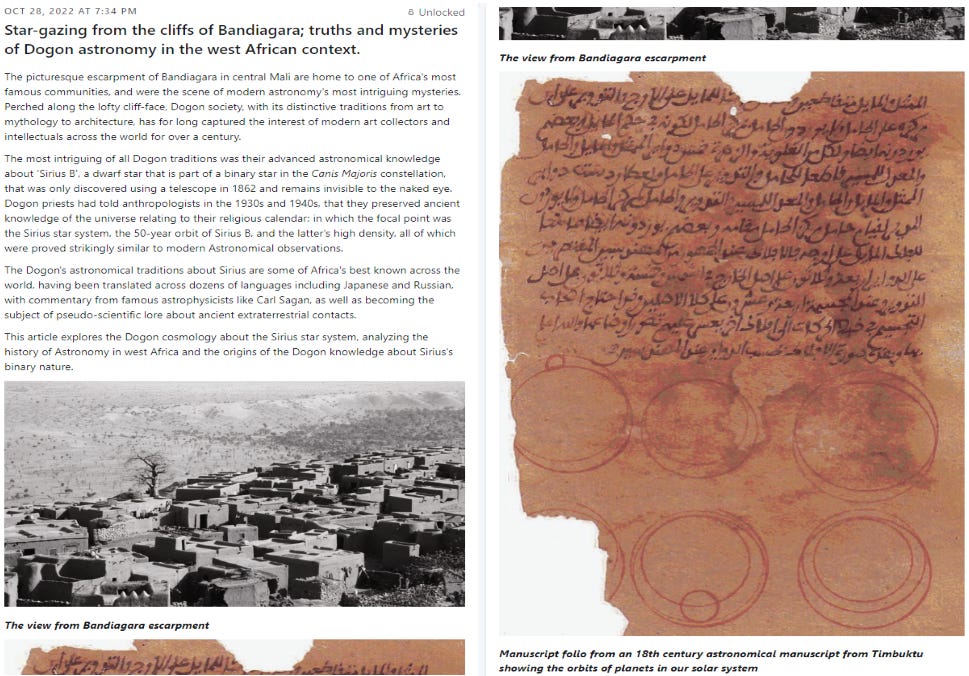

Dogon cosmology includes intriguing details about the binary star system Sirius that were only recently discovered by modern astronomers. The Dogon tradition on Sirius remains controversial among most scholars, but when combined with the history of west African astronomy at Timbuktu, it provides valuable insights on Africa’s scientific traditions.

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

Map by Anne Mayor

Une chronologie pour le peuplement et le climat du pays dogon by Sylvain Ozainne et al. pg 42

Agricultural diversification in West Africa by Louis Champion et al pg 15-16, Early social complexity in the Dogon Country by Anne Mayor.

Early social complexity in the Dogon Country by Anne Mayor. Compositional and provenance study of glass beads from archaeological sites in Mali and Senegal at the time of the first Sahelian states by Miriam Truffa Giachet

Agricultural diversification in West Africa by Louis Champion et al pg 17-18)

credit: Partners Pays-Dogon and Anne Mayor et al in “Diet, health, mobility, and funerary practices in pre-colonial West Africa”

"Toloy", "Tellem", "Dogon" : une réévaluation de l'histoire du peuplement en Pays dogon (Mali) by Anne Mayor pg 333-344, Un Néolithique Ouest-Africain by S Ozainne

Was there a now-vanished branch of Nilo-Saharan on the Dogon Plateau by Roger Blench

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg 162)

Cloth in West African History By Colleen E. Kriger pg 76-93

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg 164-165, 168)

credit: Anthony Pappone on flickr, anon

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma pg pg 153)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 92 n.8, pg 150 n.40, pg 20 n.16, 138

credits; M. Gomez, Joseph M. Bradshaw

a small section of the still unidentified “dum mountain” (possibly near Douentza) remained outside Songhai control; Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 92, 99, 147)

The following sources provide rather conflicting accounts, and its important to note that despite its location, Bandiagara wasn’t the actual zone of the Songhai-Mossi wars and was likely periphery to the Yatenga kingdom: Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 11, Traditions céramiques dans la boucle du Niger by Anne Mayor pg 113, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 185

African Dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 206-207, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick xxxix, 138, 157 n.99, 171, 175-176, )

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 89

The migration of atleast one group of artisans that eventually acquired a Dogon identity has been studied in detail by combining archeological data and oral traditions, Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 123-124

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 24, 38)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 226-227, Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 11)

credits: Kate Erza

African Worlds: Studies in the Cosmological Ideas and Social Values of African Peoples by Daryll Forde pg 89-90, Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 8)

African Worlds: Studies in the Cosmological Ideas and Social Values of African Peoples by Daryll Forde pg 99-101, Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 8, Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 18, 216, 218, 225

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 46)

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 64-66)

Variability of Ancient Ironworking in West Africa pg 300-304

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 40)

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 216)

L'architecture dogon: Constructions enterre au Mali, edited by Wolfgang Lauber, Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 228-238,

Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa by Stéphane Pradines pg 102

Dogon: Images & Traditions by Huib Blom pg 282, 286, 291, Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Timbuktu to Zanzibar by Stéphane Pradines pg 102-103

Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 12, Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by M. Nobili pg 200)

Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 12)

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 62)

Ecology and Power in the Periphery of Maasina: The Case of the Hayre in the Nineteenth Century by Mirjam de Bruijn and Han van Dijk pg 227-237

'The Chronicle of the Succession': An Important Document for the Umarian State by David Robinson pg 251, The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 5,22)

map by John Henry Hanson.

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 19, 53, 71, Forgerons et sidérurgie en pays dogon by C. Robion-Brunner pg 12)

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 53-55)

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 63, Poussière, ô poussière!: la cité-état sama du pays dogon, Mali By Gilles Holder pg 391-392 )

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 104-105)

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 107-143, Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves by Richard L. Roberts pg 158)

The Bandiagara Emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 152-160).