Among the oldest manuscripts and inscriptions written by Africans are documents relating to the study of science. The writing and application of scientific knowledge on the continent begun soon after the emergence of complex societies across the continent, from the ancient kingdoms of the middle Nile and the Ethiopian highlands, to the west African empires and East African city-states of the middle ages.

The continent is home to what is arguably the world's oldest astronomical observatory at the ancient Nubian capital of Meroe —the first building of its kind exclusively dedicated to the study of the cosmos. Meroe's astronomer-priests used a very technical approach to decan astronomy inorder to time events and predict meteorological phenomena. Their observatory complex was complete with inscriptions of astronomical equations and illustrations of people handling astronomical equipment.

Besides this fascinating piece of ancient technology, many of the continent's societies were home to intellectual communities whose scholars wrote on a broad range of scientific topics. From the Mathematical manuscripts of the 18th century scholar Muhammad al-Kishnawi, to the Geographical manuscripts of the 19th century polymath Dan Tafa, to the Astronomical manuscripts found in various private libraries across the cities of Timbuktu, Jenne, and Lamu. The history of science in Africa was shaped by the interplay between invention and innovation, as ideas spread between different regions and external knowledge was adopted and improved upon in local contexts.

This interplay between innovation and invention is best exemplified in the development of medical science in Africa. The history of medical writing in Africa encompasses the interaction of multiple streams of therapeutic tradition, these include 'classical' medicine based on the humoral theory, 'theological' medicine based on religious precedent, and the pre-existing medical traditions of the different African societies.

West Africa has for long been home to some of the continent's most vibrant intellectual traditions, and was considered part of the Islamic world which is credited with many of the world's most profound scientific innovations. The well established and highly organized regional and external commercial links which linked the different ecological zones of the region, encouraged the creation of highly complex societies, but also brought the diseases associated with nucleated settlements and external contacts.

West African societies responded to these health challenges in a variety of ways, utilizing their knowledge of materia medica and pharmacopeia to treat and prevent various diseases which affected their populations. Many of these treatments were procured locally, but others were acquired through trade between regional markets and across the Sahara. These supplemented the intellectual exchanges between the two regions, as scholars composed medical manuscripts documenting all kinds of medical knowledge available to them.

The Medical manuscripts written by west African scholars are the subject of my latest Patreon article, In which I look beyond the simple acknowledgement of the existence of scientific manuscripts in Africa to instead study the information contained in these historical documents.

Read more about it here:

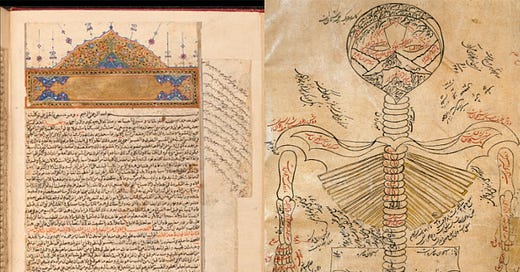

a 16th century copy of Ibn Sina’s canon of medicine originally written in 1025. Ibn Sina’s work appears frequently in the medical manuscripts of west Africa (as it does in the rest of the Muslim world as well as in Europe as Avicenna), He is one of several physicians cited by atleast two of the four west African scholars in my essay.