Introduction

When it comes to the topic of immigration, it is widely believed that assimilation is both important (normatively) and rapid and widespread (descriptively). Rapid assimilation is often simply taken for granted. For example, in economic analyses of the impact of immigration, it is not uncommon to see it assumed that second-generation immigrants have similar economic behavior as natives.1

But nowhere is the story of assimilation more important than in America, the so-called “Melting Pot.” In this piece, I will argue that the notion of widespread and rapid assimilation in America is largely a fiction. In reality, assimilation in America has been slow and incomplete. In an upcoming second part, I will argue that this is by no means specific to America.

Persistence is the norm

It’s worth first addressing more generally why rapid and widespread assimilation shouldn’t be expected. Outside the context of immigration, the reality of widespread long-run persistence has already been well-documented. Two growing scientific literatures are of particular note here.

The first of these literatures is the deep roots branch of economics. I won’t review the literature here, but the gist is that modern economic prosperity is surprisingly strongly associated with factors that long predate the Industrial Revolution (see, e.g., Spolaore & Wacziarg, 2013).

One illustrative example is that a country’s level of technological adoption in 1500 AD is strongly associated with modern national economic prosperity (Comin et al., 2010). Importantly, the migration-adjusted association is much stronger than the non-adjusted association. In simple terms, this means that development follows people, not places.

What exactly people pass down through so many generations — whether it’s culture, institutions, genes or something else — is a separate and important question, but, whatever the case, it speaks strongly to the importance of persistence beyond geographical borders.

The second is the literature on the long-run multi-generational social persistence (or mobility).2 Briefly summarized, the literature shows that social status is highly persistent, with convergence to the mean happening very slowly across generations.

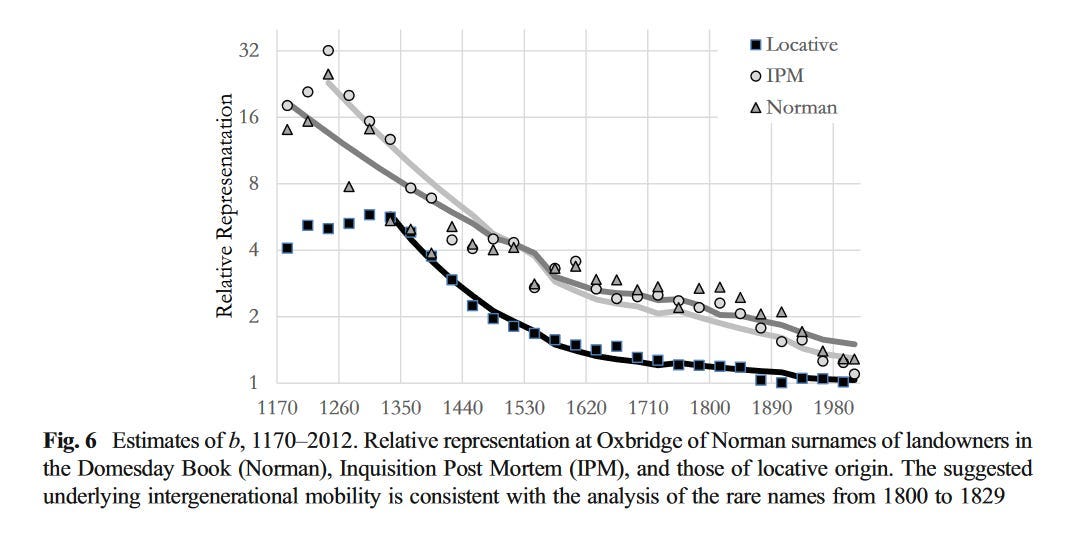

As one illustrative example, in a study using rare surnames, it was shown that people overrepresented in the Oxbridge universities had descendants that were still still overrepresented many centuries later (Clark & Cummins, 2014).

Many other studies, using a variety of methods, measures and from various countries, confirm that high persistence of social status is the norm (e.g., Barone & Mocetti, 2021; Bukowski et al., 2022; Clark, 2012; Clark & Ishii, 2012; Clark et al., 2020).

An important discovery is that naïve measures of social mobility have overestimated how mobile societies truly are. Using multi-generational data, the degree of persistence is significantly stronger than you’d predict based on simple parent-offspring correlations (Braun & Stuhler, 2018; Colagrossi et al., 2019; Adermon et al., 2021; Engzell et al., 2020).

The problem is also exacerbated by measurement error. Worse measurements, imperfect intergenerational linkage and bad data all artificially make the perceived mobility much higher than the true underlying mobility (Clark et al., 2022; Ward, 2023; Zhu, 2024). A related finding is that siblings have higher income-similarity when measured in terms of lifetime, accumulated incomes rather than income measured over a few years (Grätz & Kolk, 2022).3

We can extend these observations to the study of assimilation — measurement error and imperfect linkage across generations will lead us to overestimate the effect of intergenerational assimilation and underestimate persistence.

Further, it has been found that the inheritance of social status is highly stable in the face of external shocks and perturbations. A handful of illustrative studies include:

The enemies of the people who were sent to Gulag camps under the Soviet regime had surprisingly persistent human capital across generations (Toews & Vézina, 2025).

Inequality that existed before the Chinese communist revolutions persisted through said revolutions (Alesina et al., 2020).

Though slave wealth was nullified after the US Civil War, their sons almost entirely recovered in wealth ranking, and grandsons fully jumped back (Ager et al., 2021). A similar finding comes from the Danish West Indies (Galli et al., 2024).

The Cherokee Land Lottery of 1832 provided a large windfall to the winners. Despite that, the sons of the winners fared no better in terms of wealth, income or literacy (Bleakley & Ferrie, 2016).

The children of lottery winners in Sweden see no improvement in terms of drug consumption, scholastic performance, or skills (Cesarini et al., 2016).

In short, long-term persistence is the norm, and is surprisingly resistant to external shocks. The obvious question is: why should immigration be any different? As I’ll argue—it’s not.

The Not-so Melting Pot

Immigration and assimilation are intimately connected to the American history and identity. It is a “nation of immigrants” and part of the “American dream” was the freedom and opportunities that America could provide over other countries.

Most importantly, America is also the “The melting pot.” This metaphor speaks directly to the American assimilation story — disparate ethnic groups coming together, melting together into a singular homogeneous American culture.

We can hardly expect a metaphor to perfectly capture the complicated messiness of reality. But how much truth is there to this story? Is the American story really one of widespread and rapid assimilation? The evidence suggests no.

European immigrants

When it comes to the Age of Mass Migration (1850 to 1920s), it is often ignored that large shares of European immigrants did not “assimilate”—they returned home because they couldn’t assimilate. At least 25-40% of European immigrants returned to their home, but serious estimates as high as 60-75% exist for some decades (Bandiera et al., 2013). Return migration was also negatively selected (Abramitzky et al., 2019). Large shares of migrants could not successfully integrate, and those were typically the ones who returned. What at the surface appears to be widespread successful integration is thus to some extent a manifestation of survivorship bias.

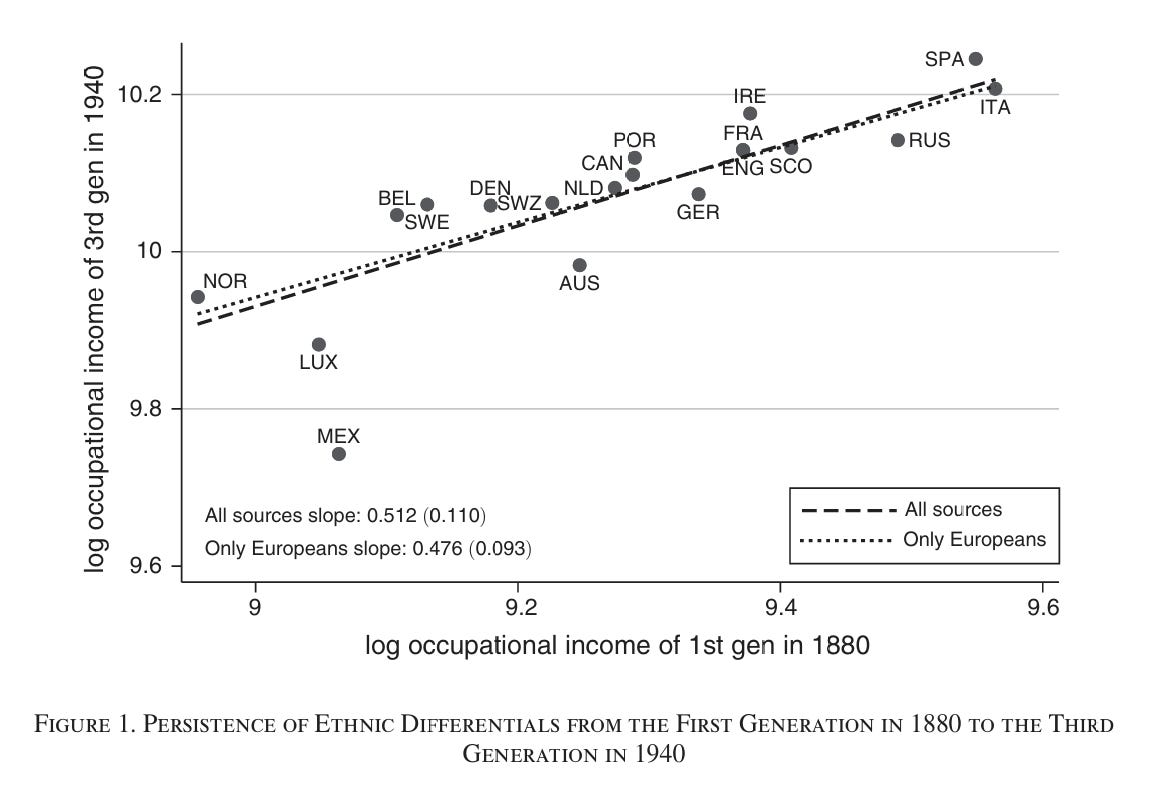

Contrary to common belief, economic disparities were also not quick to disappear. Using an impressive three-generation dataset linking immigrant grandfathers in 1880 to grandsons in 1940, Ward (2020) shows that European ethnic disparities in occupational income were strongly persistent. Ward’s study is the first to use actual linked grandparent-grandson data, and it confirms once again that persistence is stronger when high-quality data is used. As the author notes: “This result may be surprising since it is commonly believed that ethnic differentials faded quickly in the early twentieth century as in the melting pot metaphor”.

The assimilation story also ignores the fact that European immigrants did not simply arrive and passively absorb the local culture. They brought their own values and characteristics, and changed the local culture in their own image.

We all intuitively understand this when it comes to the things we are fond of — like ethnic cuisines. When Italians came to America, not only did they continue to make and eat Italian food, other Americans also began to eat more Italian food. But of course, it doesn’t just stop at food. Many studies have shown that cultural behaviors and beliefs persist across generations to some extent (e.g., Richwine, 2023; Giuliano & Tabellini, 2020).

The European differences have had long-term economic consequences which can be observed to this day. In an analysis of county ancestry compositions since 1850, Fulford et al. (2018) show that counties that received higher shares of people from more well-off countries tend to have higher GDP per-capita. Berger & Engzell (2019) have also shown that county variation in economic inequality and mobility mirrors that of their European origins.

Internal migration within the country also supports the notion that the arrival of new people can influence local customs and institutions. The Great Northward Migration of African Americans in the 20th century provides ample examples. But even the migration of Southern whites had an impact on their destinations, specifically by making them more politically conservative (Bazzi et al., 2023a; Bazzi et al., 2023b).

The successful immigrant

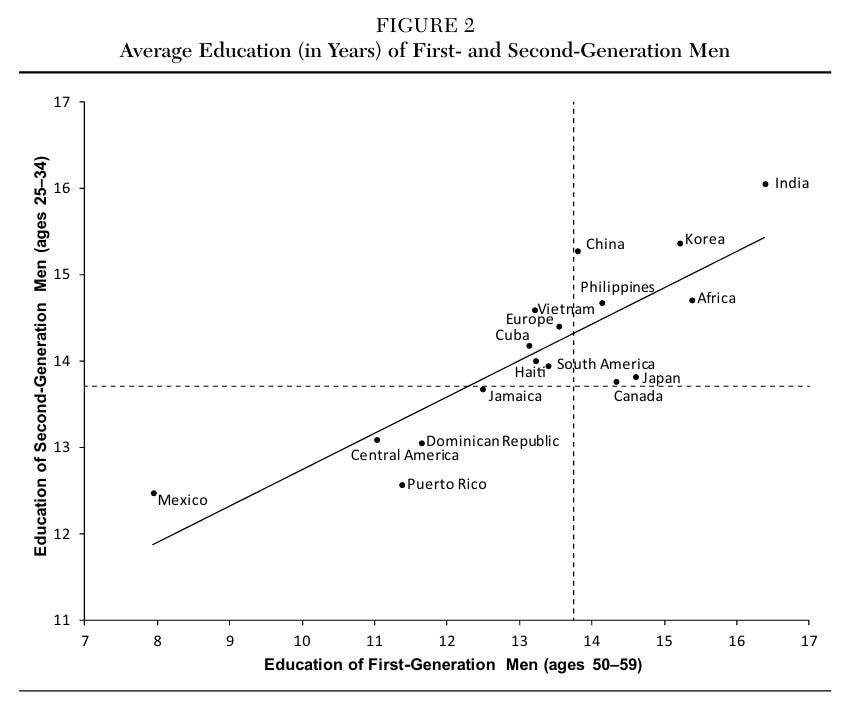

It is well known that many immigrant groups perform well economically and academically in America. Indian and East Asian immigrants, for example, significantly outperform whites in America. As a result, they are often used as examples of successful assimilation.

This argument misses the fact that those immigrants are also exceptionally positively selected on economically relevant traits. Their relative success is chiefly explained by pre-arrival characteristics (such as human capital and other correlated traits), not by traits acquired through assimilation after arrival (see, e.g., Duncan & Trejo, 2015; Hanson & Liu, 2021). Assimilation is thus given undue credit for their success.

If assimilation was really operating at great force, you’d expect rapid convergence to the average from both directions. Just as underperforming groups should improve over time, overperforming groups would expect to decline over time. But nothing indicates that Asian Americans will lose their academic and economic edge in the near future. From a normative perspective, one can certainly argue that lack of assimilation is good in this scenario. Descriptively, however, it’s yet another instance of persistence rather than assimilation.

Mexican immigrants

There is one major immigrant group that is not highly positively selected in modern times, namely Mexican immigrants (and Latin American immigrants more broadly). Consequently, their economic and academic performance is well below that of American whites.

It’s a common trope to compare Mexican immigrants with European immigrants, usually the Irish or Italians. The idea is that, while the Irish or Italian used to be dysfunctional or have poor economic performance, they rapidly assimilated and integrated into American society. A similar path should be expected for Mexicans, the proponents suggest.

This analogy does not withstand much serious quantitative scrutiny. As I’ve already shown, European economic disparities did not rapidly vanish. To expect the same of Hispanics would be to expect them not to rapidly assimilate economically.

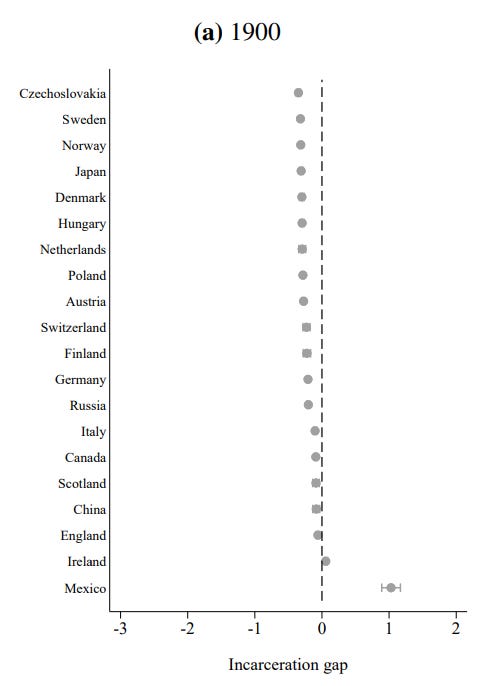

With respect to crime, the argument also doesn’t hold up. In one study, Moehling & Piehl (2009) compare the crime rates for various immigrant groups in 1904. They show that, while the Irish were overrepresented in crime, this was entirely due to minor offenses (e.g., drunkenness). In major offenses, there was no meaningful Irish overrepresentation. Italians were overrepresented in major offenses, but this overrepresentation was very modest when compared to the distinct outlier of Mexican immigrants (overrepresentation of 67% versus 432%; see Table 7). This is also consistent with more recent findings. Abramitzky et al. (2024) demonstrate that Mexicans were a clear outlier in incarceration rates among early immigrant groups in 1900-1930, and that differences between European groups were relatively small.

Looking at their data below, it becomes clear that the modern tale of massive Irish or Italian assimilation is an exaggerated fiction. European differences were real but comparatively modest—it’s not an example of great assimilation success if the differences are already slight in the first place. The disparity between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics, whether then or today, is much more substantial than this.4

But we should still address the pertinent question: do Mexicans rapidly assimilate to their non-Hispanic white counterparts?

It can be challenging to study Mexican immigration. Many are undocumented, and repeated waves of new immigrants make it difficult to distinguish between assimilation and compositional changes.

In terms of crime, it is well known that second-generation Hispanic immigrants have somewhat higher crime rates than first-generation immigrants. In that sense, they move further away from non-Hispanic whites. But how about socioeconomic outcomes?

Chetty et al. (2018) are optimistic about Hispanic economic mobility. They predict that: “Hispanic Americans are moving up significantly in the income distribution across generations. For example, a model of intergenerational mobility analogous to Becker and Tomes (1979) predicts that the gap will shrink from the 22 percentile difference between Hispanic and white parents observed in our sample to 10 percentiles for their children and to 6 percentiles in steady state.”

But can we trust this long-run extrapolation? Extrapolations are only as valid as the model used and its associated assumptions. After all, the steady state result is not something observed in the outcomes of real, breathing human beings.

One of the most important lessons of the social persistence literature is that multi-generational persistence is much greater than what you’d predict based on correlations between parents and children, such as Becker-Tomes style models (Braun & Stuhler, 2018; Colagrossi et al., 2019; Adermon et al., 2021; Engzell et al., 2020). More precisely, the Becker-Tomes model predicts faster-than-geometric decay over generations, whereas the true (empirically observed) decay is slower-than-geometric (Solon, 2018).5

It would be a great mistake to optimistically extrapolate from the jump between first- and second-generation to subsequent generations. Common sense tells us that the first jump is distinct from all subsequent generations, as only first-generation immigrants are born outside the country.6

Evidence also supports that there is stalling beyond the first generation for Latino immigrants. Villarreal & Tamborini (2023) show that incomes for second-generation Latino immigrants grow less with age, stalling relative to other immigrant group descendants.7 Moreover, third-generation Hispanic men seemingly perform worse than second-generation Hispanic men.

The findings of a unique and impressive study are particularly illuminating regarding historical Hispanic assimilation. In their 2008 book, Telles & Ortiz were able to follow Mexican immigrants and their actual descendants across several generations.8 Contrary to the authors’ expectations, there was little support for the assimilation narrative: “the educational progress of Mexican Americans does not improve over the generations […] our data show no improvement in education over the generation-since-immigration and in some cases even suggest a decline.” Concerning college completion rates, they write: “Sadly and directly in contradistinction to assimilation theory, the fourth generation differs the most from whites.”

All taken together, there is little reason to expect that economic, educational and criminal disparities between (non-Hispanic) whites and Hispanics will vanish any time soon. Yes, there is a significant boost from first- to second generation, but any subsequent generational improvements are much more modest and less systematic.

The elephant in the room

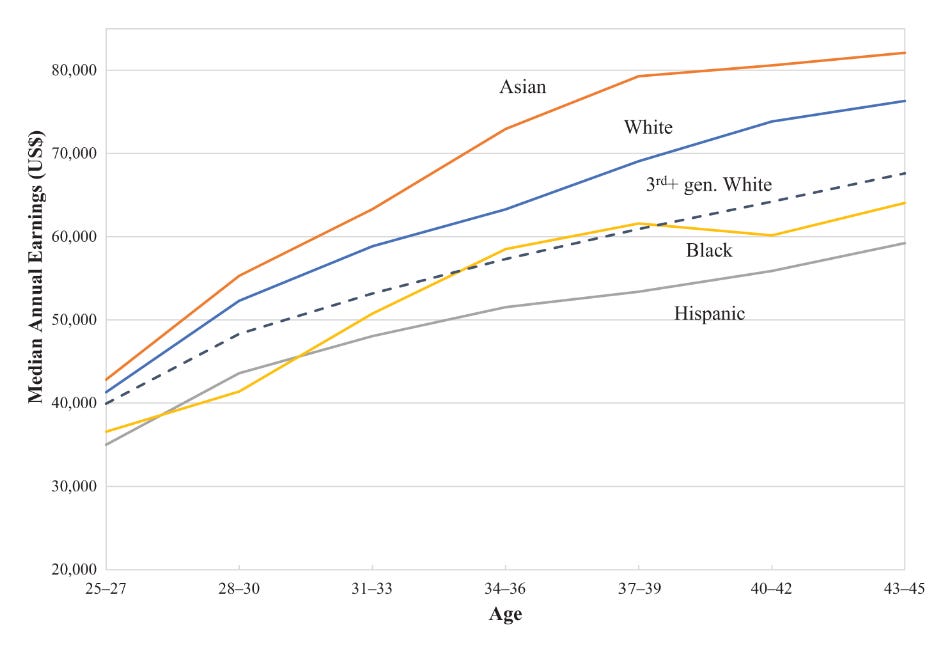

Setting aside European, Asian and Hispanic immigrants, there is a much more glaring problem with the American assimilation narrative—the persistent American underclasses, black Americans and Native Americans.

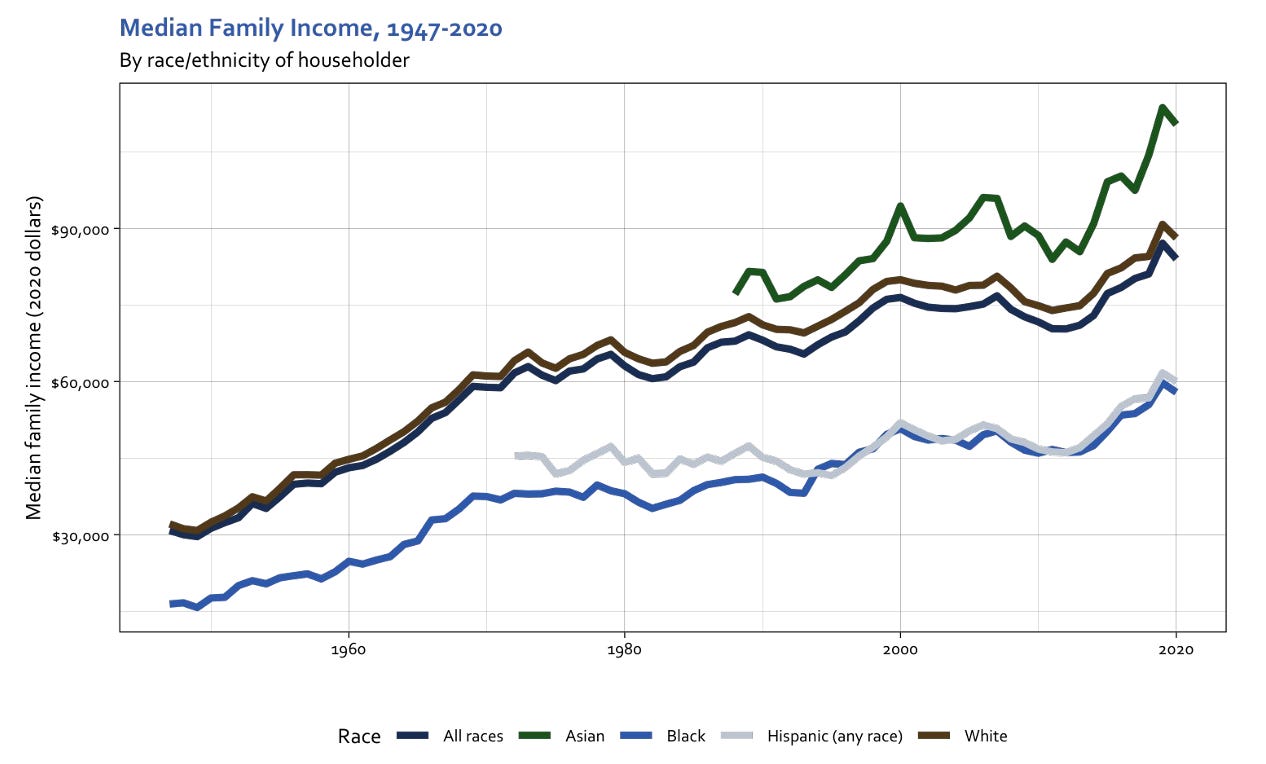

It is well known that large black-white disparities exist in important domains such as economics, education and crime. And, as the example of household income below shows, there has been little convergence with respect to some important measures for over 70 years.9

Yet people rarely appreciate this relevant fact in discussions of assimilation. Some will surely object to this argument on account of African Americans not being immigrant groups. But this makes the example even more striking, not less. Having lived together so long — and yet so large disparities persist — clearly speaks to America’s inability to integrate and assimilate disparate groups of people.

Conclusion

Evidence shows that social status persists strongly across multiple generations. Much the same applies in the context of immigration assimilation: multi-generational persistence is the norm, with only very gradual convergence that can easily take well over 100 years. The better the data and measurements, the stronger the persistence. While there is often a significant jump from first- to second-generation, subsequent generations do not experience large systematic boosts.

Contrary to popular opinion, the Age of Mass Migration was not a period of widespread and rapid assimilation. Large shares of European immigrants left the country because they couldn’t successfully integrate, and, among those who stayed, disparities were not quick to fade. Immigrants also played an important role in shaping America’s trajectory, rather than merely passively assimilating.

Today, many immigrant groups are highly successful in the United States — much more successful than US-born natives. This, however, is not explained by some assimilation process after arrival, but by their pre-arrival characteristics due to national origin and extreme selectivity.

The prediction that Mexican immigrants will rapidly assimilate to their non-Hispanic white peers is also unlikely to come to fruition. The analogy between Mexican immigrants and former European immigrants is flawed for two reasons. First, it exaggerates how different European ethnic groups were in the past. In reality, their differences were comparatively modest. Second, it exaggerates how quickly European immigrant groups assimilated. These two exaggerations together create a false image of massive and rapid convergence which simply isn’t historically accurate. Historical multi-generational data on Mexican immigrants and their descendants is also consistent with persistence rather than rapid assimilation.

Lastly, the elephant in the room is that of the persistent underclasses in America, namely African Americans and Native Americans. Despite living in the same country for many generations, large disparities persist between black and white Americans. These disparities will also not disappear any time soon.

While the melting pot metaphor sounds appealing, it is largely a fiction. America is not a place where widespread and rapid assimilation occurs. This should not be taken as a slight, however, for I am not claiming this is particular to America.

The upcoming second part of this article will address exactly this. Using data from a variety of countries, I will argue that lack of quick and widespread assimilation is the norm, not the exception.

Just to provide one example, Holmøy & Strøm (2014) assume this in an analysis of Norwegian data, saying: “the immigrants’ children are assumed to have the same economic behaviour as the non-immigrants.”

Much of the evidence is reviewed in Gregory Clark’s book The Son Also Rises.

Clark, in The Son Also Rises, goes further: he suggests that any socioeconomic indicator, however well-measured, is still only a proxy of a kind of “latent” social status. This latent factor, he suggests, persists much more strongly than any individual indicator analyzed on its own. This is a good insight, but I’m not convinced that persistence coefficients as high as 0.7-0.8 consistently replicate, even with methods addressing this point.

The age-adjusted rate of imprisonment is about 2-and-a-half times bigger for Hispanics than for non-Hispanic whites. See the BJS report on prisoners (“Prisoners in 2021”). As Figure 4 shows, Hispanic males have substantially higher incarceration rate than (non-Hispanic) white males, even after adjusting for age. You can also see the incarceration rates over time in Figure 3 in a different BJS report (“Prisoners in 2022”).

Geometric decay means that if the parent-child correlation (in, say, income) is 0.30, you’d expect the grandparent-child correlation to be 0.30², or 0.09. Empirically, multi-generational persistence is stronger than this (i.e., the grandparent-child correlation would be substantially larger than 0.09). See, e.g., Engzell et al. (2020).

Historically, cross-sectional evidence has also found much larger differences (in terms of income and education) between first- and second-generation Latino immigrants than between second-generation and subsequent generations. Because it isn’t following people and their own descendants, comparisons between 1st, 2nd and 3rd+ generation immigrants are affected by compositional effects and therefore not perfect. Still, though imperfect, the evidence is consistent with the view that changes between generations beyond the first are smaller than the change between first- and second-generation.

For Chetty’s et al.’s analysis, measuring income between age 31 and 37, this plausibly means that the level of convergence has been overestimated.

The fact that they follow descendants from immigrants means that it can clearly distinguish between generational assimilation and compositional changes due to new immigrant arrivals.

Importantly, the vast majority of African Americans are not new immigrants, and are instead descendants of people who have been in the United States for a long time. This means that the changes over time have only been minimally affected by compositional effects due to new arrivals.

This shows how out of touch with reality Richard Hanania and other Classical Liberal are about assimilation into Western Civilization

This aligns with genetics. Namely, someone from southern Italy is more closely related to someone from Scotland than they are to someone from the middle east, despite outward appearance.