Africans were already present on the European mainland by the time Herodotus —the so called father of history— wrote his monumental work, The Histories.

Herodotus' account mentions the presence of Aithiopian and Egyptian auxiliaries in the armies of the Persian emperor Xerxes at Doriscus and Plataea in 480 BC. Herodotus also provides a description of the land of Egypt and Aithiopia where these auxiliaries originated, and the includes the first external account of the aithiopian capital Meroe in what is today Sudan.1

Aithiopia was a classical term for the land south of Egypt, corresponding to the ancient kingdom of Kush, but the term was in later periods also applied more generally to Africans living beyond the southern Mediterranean coast.2 Greek myths and literature give a prominent place to aithiopians, and their frequent representation in artwork from the 5th century BC onwards was doubtlessly influenced by direct contacts with Africans, both in Africa and in Greece.3

Terracotta statuette of a seated African holding a scroll. ca. 300-200 BC, Apulian (Greek) No 1856,1226.312, British Museum. Terracotta figure of an African actor or priest. 2nd-1st century BC, Smyrna, Turkey. No. 1993,1211.1, British Museum. Bronze vessel in the form of the head of a young African woman. 2nd-1st century BC. Hellenistic. No. 1955,1008.1 British Museum.

While my previous essays on African explorers who travelled across the old world from Rome to China focused on those Africans whose origin and careers were sufficiently known and documented, they excluded the more abundant iconographical evidence and fragmentary textual accounts which suggest a much larger community of diasporic Africans than is commonly averred.

Aithiopians appear for the first time in Greek literature in the Homeric poems of the 8th century BC, albeit with semi-mythological attributes. They are more accurately described in the accounts of Xenophanes (d. 478 BC), Herodotus (d. 425 BC), and the Athenian dramatists of the time who included them among the subjects of their plays and poems about the semi-legendary figures Memnon and Busiris. Aithiopians are also reported among the disciples of the philosophers Aristippus (d. 356 BC) and Epicurus (d. 270 BC).4

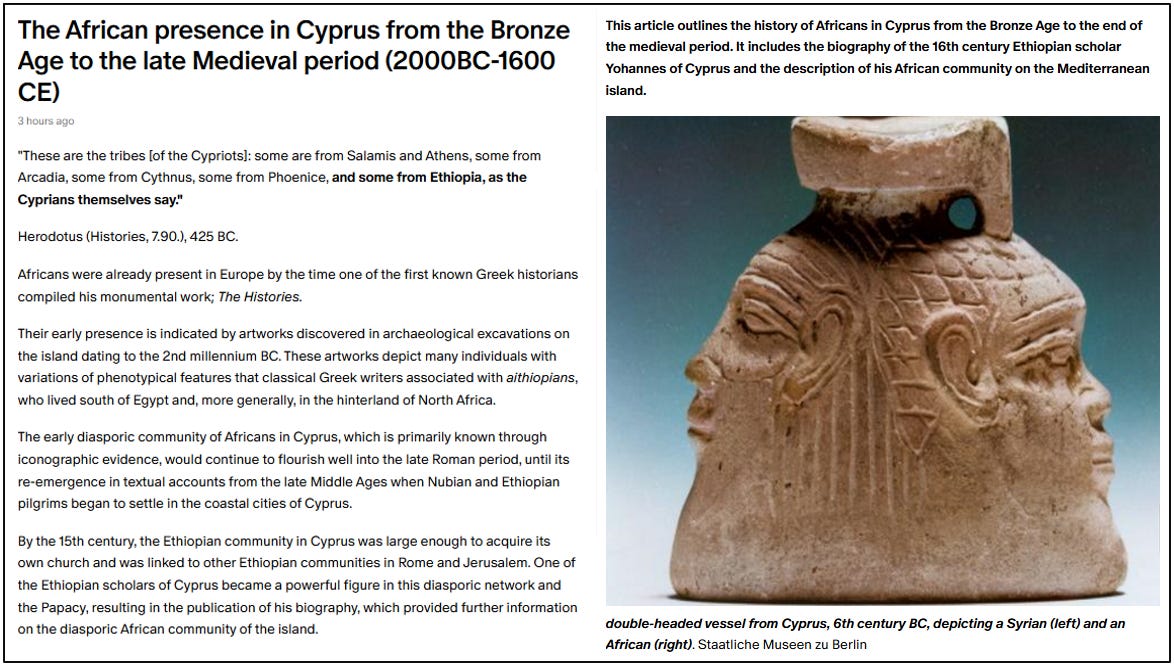

Images of Aithiopian figures appear much earlier in the northern Mediterranean, first on the island of Cyprus in the early 2nd millennium BC, and later on mainland Greece by the 6th century BC. Classical artists depicted aithiopian figures on virtually every medium, including marble, bronze, and terracotta sculptures; Janiform vases that juxtaposed aithiopians with Thracians and Scythians; black-figure vases; as well as masks and other items which point to the presence of aithiopians in ancient Greece.5

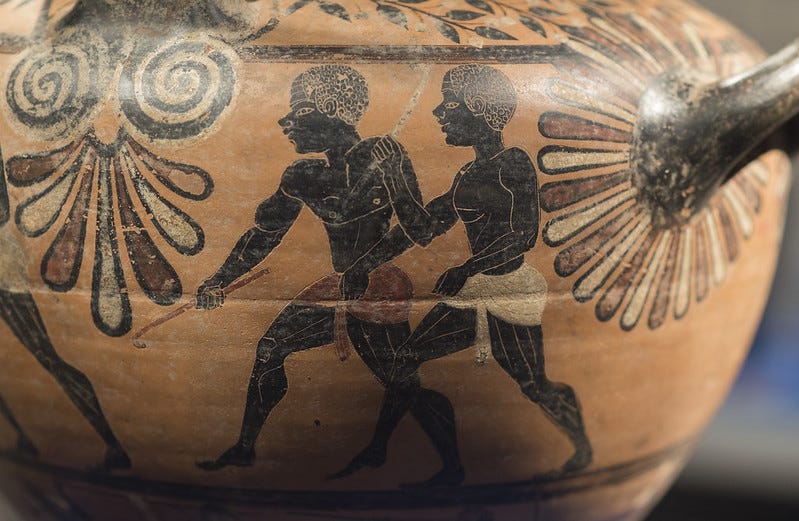

aithiopian soldiers, detail from a Black Figure table amphora by painter Exekias depicting Achilles fighting Penthesileia and Memnon with aithiopians, c. 535 BCE. No. 1849,0518.10. British Museum.6

aithiopian soldiers coming to the assistance of King Busiris of Egypt, detail from the Caeretan hydria by the Busiris Painter depicting Herakles fighting Egyptian priests and soldiers of Busiris. c. 550 BCE. Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna 3576. Flickr image by Dan Diffendale. ‘The vase deliberately aims to capture Egypt’s human diversity: the priests range in skin color, hair color, and face shape, while the soldiers are all depicted using a register very similar to Exekias’ portrayals’.7 (see the vase above)

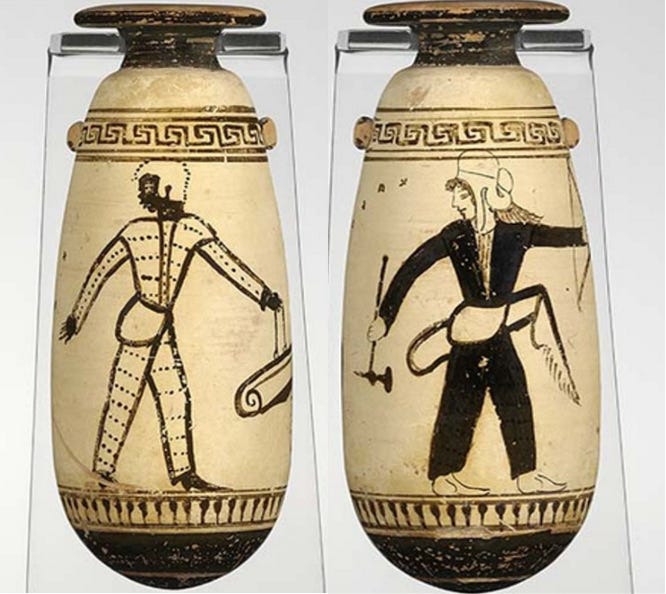

Alabastron depicting an aithiopian man and a Scythian (amazon) woman. ca. 490-480 BC. No. 3382. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.8

The aithiopian figures from Cyprus represent the earliest iconographical evidence of Africans in the diaspora. The island of Cyprus was associated with aithiopians during the classical period, and aithiopians were counted among the ‘founding tribes’ of Cyprus in Herodotus’ account.

The presence of Africans in Cyprus is better documented during the late Middle Ages, when its cities of Nicosia and Famagusta became home to a community of scholars and pilgrims from medieval Nubia and Ethiopia, who produced influential figures in Rome during the Counter-Reformation.

The history of the African diaspora in Cyprus from the bronze age to the late medieval period is the subject of my latest Patreon article.

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Herodotus' Histories, 7.69-70, 9.32, 2.29

Herodotus in Nubia By László Török, Greeks and Ethiopians by Frank M. Snowden in J. E. Coleman and C. A. Walz (eds.), Greeks and Barbarians: Essays on the Interactions between Greeks and Non-Greeks in Antiquity and the Consequences for Eurocentrism

Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience By Frank M. Snowden pg 1-14, 123-129, 184-185

Before Color Prejudice: The Ancient View of Blacks By Frank M. Snowden pg 46-49, 93-94

Blacks in Ancient Cypriot Art by Vassos Karageorghis, Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience By Frank M. Snowden. For a more nuanced interpretation of pre-6th century aithiopians in Greek and Cypriot artwork, see; Racialized Commodities: Long-Distance Trade, Mobility, and the Making of Race in Ancient Greece, C. 700-300 BCE by Christopher Stedman Parmenter pg 89-122

Racialized Commodities: Long-Distance Trade, Mobility, and the Making of Race in Ancient Greece by Christopher Stedman Parmenter pg 96-97

Racialized Commodities: Long-Distance Trade, Mobility, and the Making of Race in Ancient Greece by Christopher Stedman Parmenter pg 95-96

Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience By Frank M. Snowden pg 25

I commend you for using the term African, and not "black." As long as we get continue to use this binary (Anglican) racial oversimplification, we are consigning ourselves to mental slavery and discrimination. In fact the terms, Kushitic or Nilotic is even better than African or Eithiopian becuase they do not reflect Eurasion influences.

With Abyssinia changing its names to Ethiopia, modern Ethiopia became associated with:

The Queen of Sheba

The first Christian empire in Africa

Ancient “Aethiopians” mentioned by Greeks, Romans, and in the Bible

Meanwhile, Sudan — the actual site of Kush, Meroë, the Black Pharaohs, and powerful queens like Amanirenas — was relegated to colonial language like “Anglo-Egyptian Sudan,” then “Sudan” (which just means ‘land of the Blacks’ in Arabic).

So isnt that, in a postcolonial, cultural sense, a kind of theft? Or at least a misnaming that led to the misplacement of pride, heritage, and narrative.